Run your finger down the list of credits for a major restoration project or historic courthouse in Texas, and you won’t be surprised to spot a distinctive name belonging to three generations of Japanese-American builders: Komatsu.

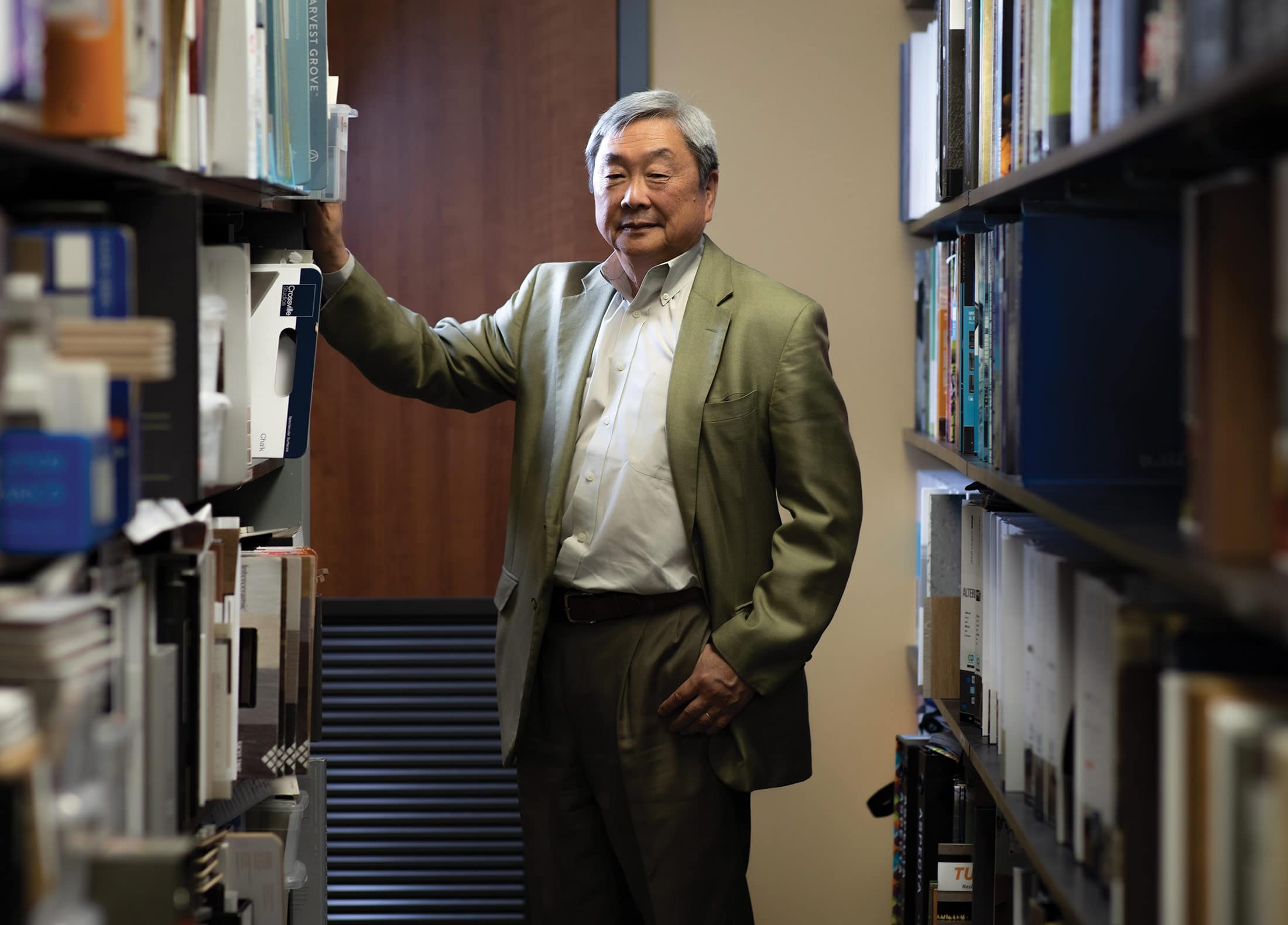

Easygoing and unassuming, Karl A. Komatsu, current leader of the family firm, has contributed to some of Texas’ most influential architectural designs. His steady hand and commitment to heritage have formed a lasting impression on the state’s built environment, one that will endure for years to come.

On the day we meet in Komatsu’s Fort Worth office, overlooking the Trinity River, we’re greeted at the door with a warm smile. Karl’s presence is friendly and relaxed, and his welcome is genuinely hospitable.

Our conversation begins with a little history. Karl is a third-generation immigrant—sansei, in the Japanese-American vernacular. His grandfather, Hisakichi Komatsu, was born in Japan in 1887, arriving in the United States in 1900 as a member of the Japanese merchant marine. Bright and industrious, Hisakichi went to work for the Spokane-Seattle Railroad, landing a position as foreman because of his ability to communicate in English as well as Japanese, a bit of Cantonese, and other Asian tongues. As was customary in Hisakichi’s culture, his family arranged his marriage. Hisakichi returned to his native country to marry Kofusa Honda, and she soon joined him in Portland, Oregon, in 1921.

PERSECUTION AND PERSERVERANCE

Karl’s father, Albert, was born in Portland in 1926, the second of the Komatsus’ three children. When U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, authorizing the internment of citizens of Japanese ancestry and resident aliens from Japan, the Komatsu family were taken to Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles in January 1943. It was a trying time for Japanese-Americans, who were born with full rights of citizenship yet treated as threats during wartime. Families were separated, homes were seized, and workers were assigned to menial jobs — yet many, like the Komatsus, endured hardships and eventually reestablished better lives in the U.S.

Family members were scattered among several internment camps. “My father, Albert, my mother, and my two sisters were assigned to a camp installation in Idaho,” Karl explained.

“Determined to avoid internment, my father was ultimately deemed of national interest because of his railroad construction experience and allowed to remain on the job.”

Agricultural production was essential to providing food in the camps as well as to the national economy. Young Albert and his older sister were allowed to leave, having signed a federal affidavit agreeing to work only with agricultural teams growing and harvesting crops. Albert’s mother and his younger sister, however, remained in the camp until 1946.

“On account of his exceptional mathematics skills Albert was recruited to join a special intelligence unit in northern Minnesota assigned to develop a device similar to the Enigma machine.”

Eventually released, Albert’s older sister assumed a teaching position in Minneapolis–Saint Paul. Albert, too, was released and allowed to join his sister in Minnesota to complete his high school education. Boarding at the YMCA until he turned 18 because his sister was unable to provide living accommodations, Albert soon received a draft notice from the U.S. Army.

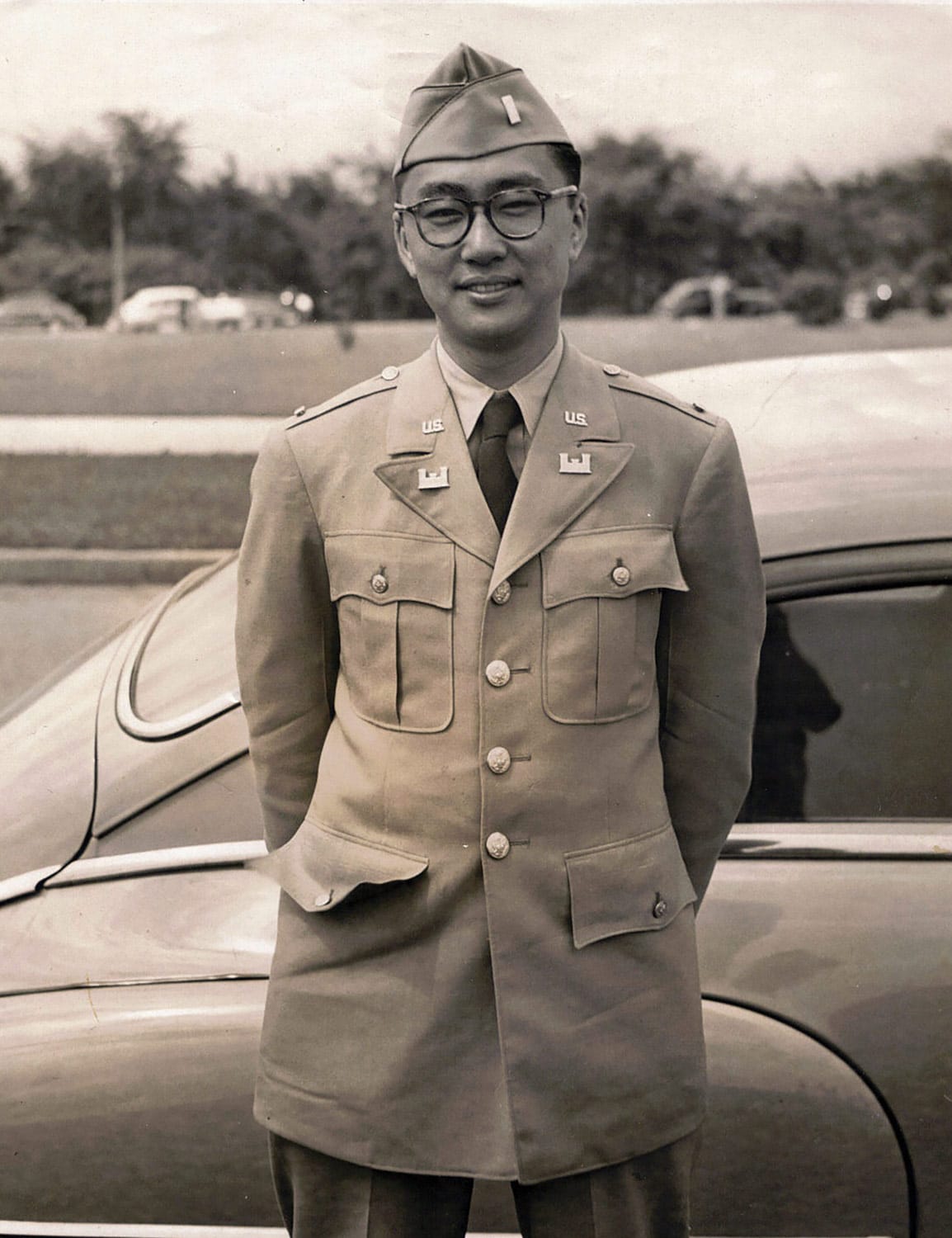

On account of his exceptional mathematics skills Albert was recruited to join a special intelligence unit in northern Minnesota assigned to develop a device similar to the Enigma machine. He enlisted in the engineering group but was assigned to army installations around the U.S., auditing and reconciling accounting procedures.

Following his discharge in 1947, Albert enrolled in college under the G.I. Bill. Still unable to afford his first choice, the mathematics program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he returned to Minneapolis and enrolled in the University of Minnesota, where he earned his degree in architecture. It was at the university that Albert met and wed Karl’s mother, Toyoko ‘Toy’ Tanaka, the youngest of ten children born in Hawaii of Japanese parentage, and an ancestry that Japanese scrolls trace as far back as the 1600s.

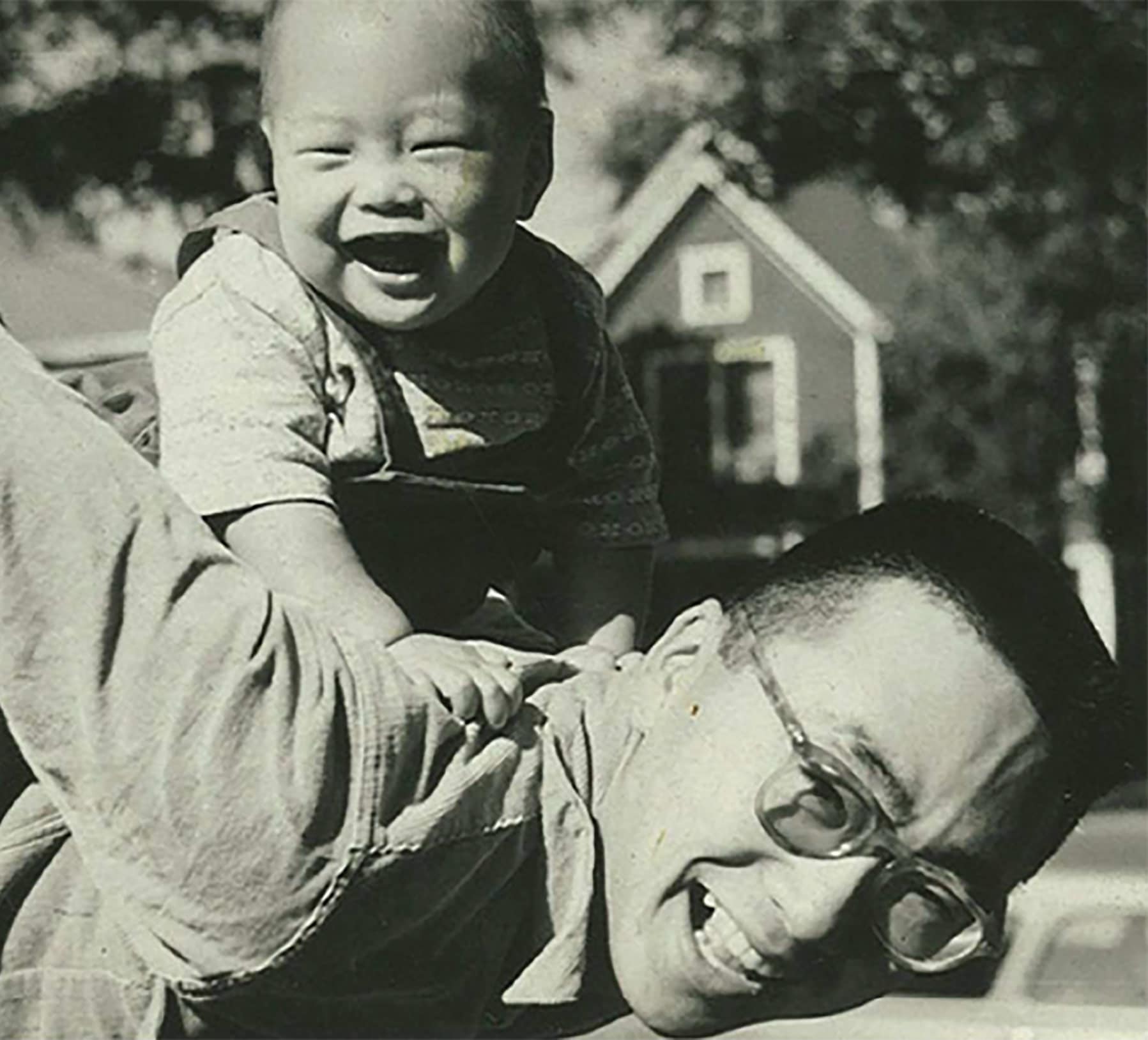

Albert was soon recalled to service during the Korean War. Karl was born in Minneapolis while his father was serving in the military, but the family was reunited and were moved stateside to what was then Camp Wolters Helicopter Training Facility in Mineral Wells, Texas, where they remained until Albert’s discharge in 1954.

Only then was Albert free to pursue a career in architecture, working first in Dallas for the prominent George Dahl Architectural Firm (best known for the Art Deco buildings of Fair Park) and then in Fort Worth with Wyatt Hedrick of Sanguinet, Staats, and Hedrick, designers of Love Field, among other major projects, before opening his own office in 1959.

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON

Karl grew up in Fort Worth knowing how his father made his living, but contrary to the Japanese custom of sons following fathers in a family business, he was not particularly pressured to adopt the tradition.

“The joke,” Karl notes, “was that my father wanted me to become a doctor or lawyer so he might retire comfortably at an early age.” Only at age 80 did the elder Komatsu retire, in 2006—though he still works providing expert witness testimony on behalf of construction companies, architects, and engineers.

So when Karl made the decision in high school to study architecture, he sought his mother’s counsel, wondering just how badly he’d let his father down. Quite the opposite was true, she assured him; his father would have been disappointed had Karl not decided to pursue a career in architecture!

[adsanity id=”1029″ align=”alignnone”/]

Karl enrolled at the University of Virginia in the fall of 1970. He chose Charlottesville because he was eager to meet new people and loved the natural beauty of the area. The curriculum leaned heavily toward Jeffersonian architecture, and Karl’s studies included attendance at the university’s affiliate International Centre for Palladian Studies in Vicenza, Italy. While he appreciated classical design, Karl was also influenced by the mid-century and Japanese styles he grew up with, as well as expressive modernist forms.

Graduation came on the heels of a recession in the U.S., and Karl worked with several East Coast firms before settling in Washington, D.C. There, he recalls, his appreciation for restoration and preservation evolved “more or less by osmosis.” He worked for a time with the independent firm of Harry Weese & Associates, a well-known advocate of historic preservation and the foremost designer of rail systems at the time, whose works included D.C.’s Metro. Assigned to work on the master plans of several historic stations between Washington and Boston as part of the Northeast Corridor High Speed Rail Improvement Program, Karl found his interest in historic conservation and adaptive reuse growing.

By 1978 Karl had opened his own architectural firm in D.C. despite warnings about the challenges of working in such a temperamental business climate both commercially and politically. He grew his business, building an impressive portfolio of federal work along the way until merging his Washington firm with his father’s Fort Worth business in the early 1980s.

SUCCESSES IN TEXAS

There, the family were happy to be reunited once more.

Under Albert’s leadership, Komatsu Architecture had become widely recognized for contributions to some of Fort Worth’s most endearing projects, including most of the structures in the Japanese Garden at the Botanic Gardens and civic buildings like the city’s Fire Station No. 8 on Rosedale. In addition to the firm’s endeavors in local and state preservation activities, Karl received a two-year appointment to serve on the National Park System Advisory Board under the George H. W. Bush Administration, reporting to the Secretary of the Interior. His duties in that capacity included reviewing national historic register and natural resource grant nominations.

By the 1980s Karl’s reputation as a preservationist was acknowledged by then Governor Bill Clements, who in 1987 appointed him to the Texas Historical Commission (THC). He was reappointed by Governor Ann Richards in 1993 to serve as chairman.

Komatsu’s Courthouses

- Wise County Courthouse

- Lakes Trail Region

- 106 S. Trinity St.

- Decatur, TX 76234

- (940) 393-0340

- co.wise.tx.us

- Hours: Monday-Friday, 9 am–4 pm

- The Decatur courthouse was designed by architect J. Riely Gordon of New York and built in 1895. The first court was held in the new building in December 1896. Photo: Jim Bell

- Throckmorton County Courthouse

- Forts Trail Region

- 121 N. Minter Ave.

- Throckmorton, Texas 76483

- (940) 849-4411

- throckmortontx.org

- Hours: Monday-Friday, 9 am–4 pm

- The Throckmorton County courthouse design reflects an Italianate styling and features polychromatic walls of tan- and buff-colored quarried sandstone and a mansard roof with a square cupola. Photo: Wayne Wendel

- Parker County Courthouse

- Lakes Trail Region

- 1 Courthouse Square

- Weatherford, TX 76086

- (817) 598-6195

- parkercountytx.com

- Hours: Monday-Friday, 9 am–4 pm

- The 1886 Parker County Courthouse was designed by architect W. C. Dodson. The style and design are similar to those of his other Texas courthouses in Hill, Hood, and Lampasas counties. Photo: Wayne Wendel

- Lampasas County Courthouse

- Hill Country Trail Region

- 501 East Fourth St.

- Lampasas, TX 76550

- (512) 556-8271

- co.lampasas.tx.us

- Hours: Monday-Friday, 8 am–5 pm

- The Second Empire–style courthouse, completed circa 1883–84, was the design of W. C. Dodson. The courthouse was restored by Komatsu Architects and the building rededicated in 2004. Photo: Texas Historical Commission

Preservation of historic architecture and archeological sites faced serious challenges to preservation at the time, and in response the 71st Legislature established the Texas Preservation Trust Fund in 1989. As a commissioner, Karl played a role in creation of the trust that awards competitive matching grants annually to qualified applicants to preserve architectural and archeological treasures throughout the state of Texas. He also participated in early planning for what was to become the Texas Historic Courthouse Preservation Program. “In my last year as chair of the THC,” recalls Karl, “I spent over 200 days in Austin.”

Karl’s service on the THC caught the attention of President George H. W. Bush, and he followed one of Fort Worth’s most influential leaders, Ruth Carter Stevenson, creator of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, as trustee on the board of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In addition to providing leadership and advocacy for revitalization of America’s historic places, the trust works on policy and local preservation campaigns through affiliated agencies including the National Park Service and state historic offices nationwide. Karl would serve nine years on the board, under two presidential administrations.

In the early years of the Clinton administration, the president created the National Performance Review, a federal initiative with the goal of creating a government that “works better and costs less.” Vice President Al Gore led the task force, forming teams to evaluate and make recommendations on the operations of hundreds of departments and governmental agencies. Karl was appointed to chair the task force to undertake review of federal historic preservation, creating guidelines for preservation offices in all fifty states.

The post did have its perks, Karl remembers. “All our meetings were held in National Parks across the U.S., which made for some pretty extraordinary backdrops,” he says—but also for critical issues ranging from privatization of national historic sites such as the Presidio in San Francisco and the redevelopment movement that threatened the Little Tokyo Historic District in Los Angeles, and, at home, Dallas’ proposed Sixth Floor Museum. When proponents of the Dallas museum proposal came up against factions that viewed the project as glorification of a national tragedy, Karl weighed in. For those who really care, he argued, the museum was “not about politics, it’s history—no matter how glorious or tragic.”

When the museum opened in 1989, members of the John F. Kennedy family expressed appreciation for the efforts put forth by the Dallas County Historical Foundation and the THC.

COURTHOUSES AND COUNTDOWNS

One of the THC’s most revered initiatives—and one near and dear to Karl Komatsu’s heart—is the Texas Historic Courthouse Preservation program. Since its establishment in June 1999, the project has provided assistance to seventy of the state’s more than 240 courthouses, all at least fifty years old. Karl notes that, while there were many project collaborators over the years, “the THC staff should be credited with recognizing the dangers and need for protection, especially after courthouse fires such as those in Hill and Newton Counties.”

Komatsu Architects’ first courthouse project was in the central Texas county of Lampasas, in the city of the same name. The earliest of Waco designer W. C. Dodson’s courthouses, the 1884 structure had survived natural disasters over the years, but “very nearly didn’t survive the awful repairs made over time,” lamented Karl. Repairs performed by numerous engineers covering very different generations of construction complicated the project and threatened its success. The Lampasas edifice, third oldest in the state still functioning as a courthouse, was rededicated on March 2, 2004, the 169th anniversary of the Declaration of Texas Independence.

Komatsu Architects has gone on to work on several other courthouses around the state, including projects in Marion, Parker, Glasscock, Cooke, Wise, and Lynn counties.

Karl’s career has spanned nearly 50 years and is distinguished by a reverence for, and deep-rooted commitment to his cultural heritage and preservation of our state and national history. Of the projects he considers personal triumphs he is surprisingly modest, focusing on collaboration and relationships. Review of possible environmental impacts of airport noise on historic resources, early conversations surrounding preservation and restoration of NASA’s Apollo Mission Control Center, creation of the Texas Preservation Trust Fund that was established during his time on the THC, and his work restoring some of Texas’ historic courthouses are just a few of his contributions. Karl is particularly proud of his association with current THC chairman, John L. Nau III, who followed Karl as chair of the THC in 1995 and returned to chair the commission again in 2015. As Karl notes, “John is a marketing genius who has seized on heritage tourism and turned Texas history into an economic driver.”

Karl and his wife, Nancy, live in Fort Worth and have two sons, Brice and Christopher. Karl’s younger sister, Sylvia, is chief content officer for KERA and KXT public broadcasting stations in Dallas.

The elder Komatsu, Albert, still stops by the office on occasion—“mostly to check in and visit,” quips Karl. As we depart, he brushes aside questions about his own plans for retirement, saying simply, “There is so much more to be done . . . work in preservation has been like a continuing education, so it hasn’t been a chore, it’s really been a privilege.”