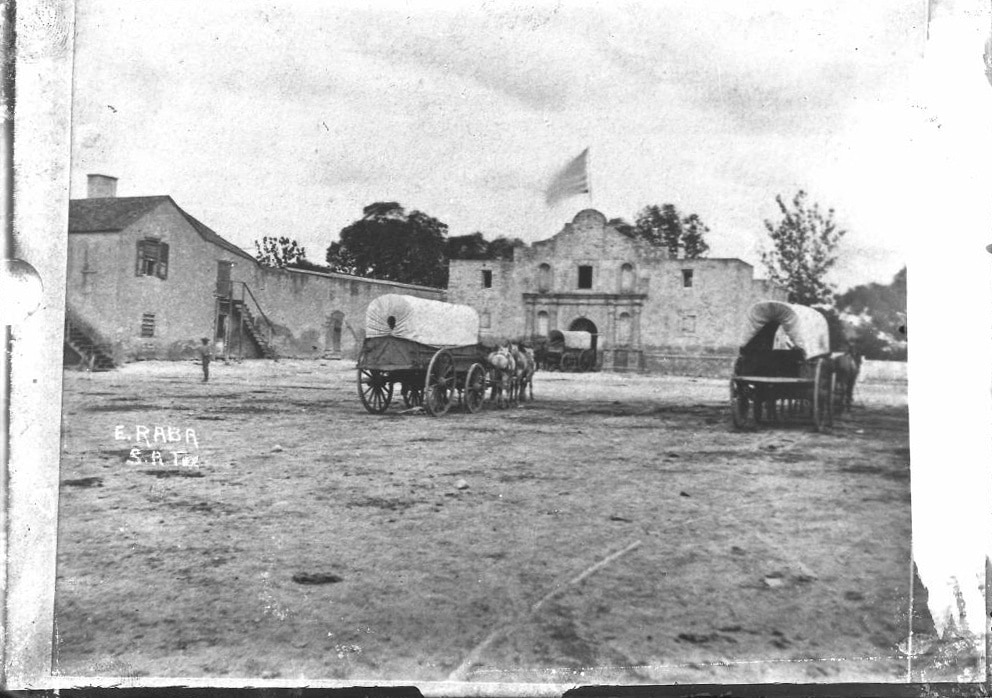

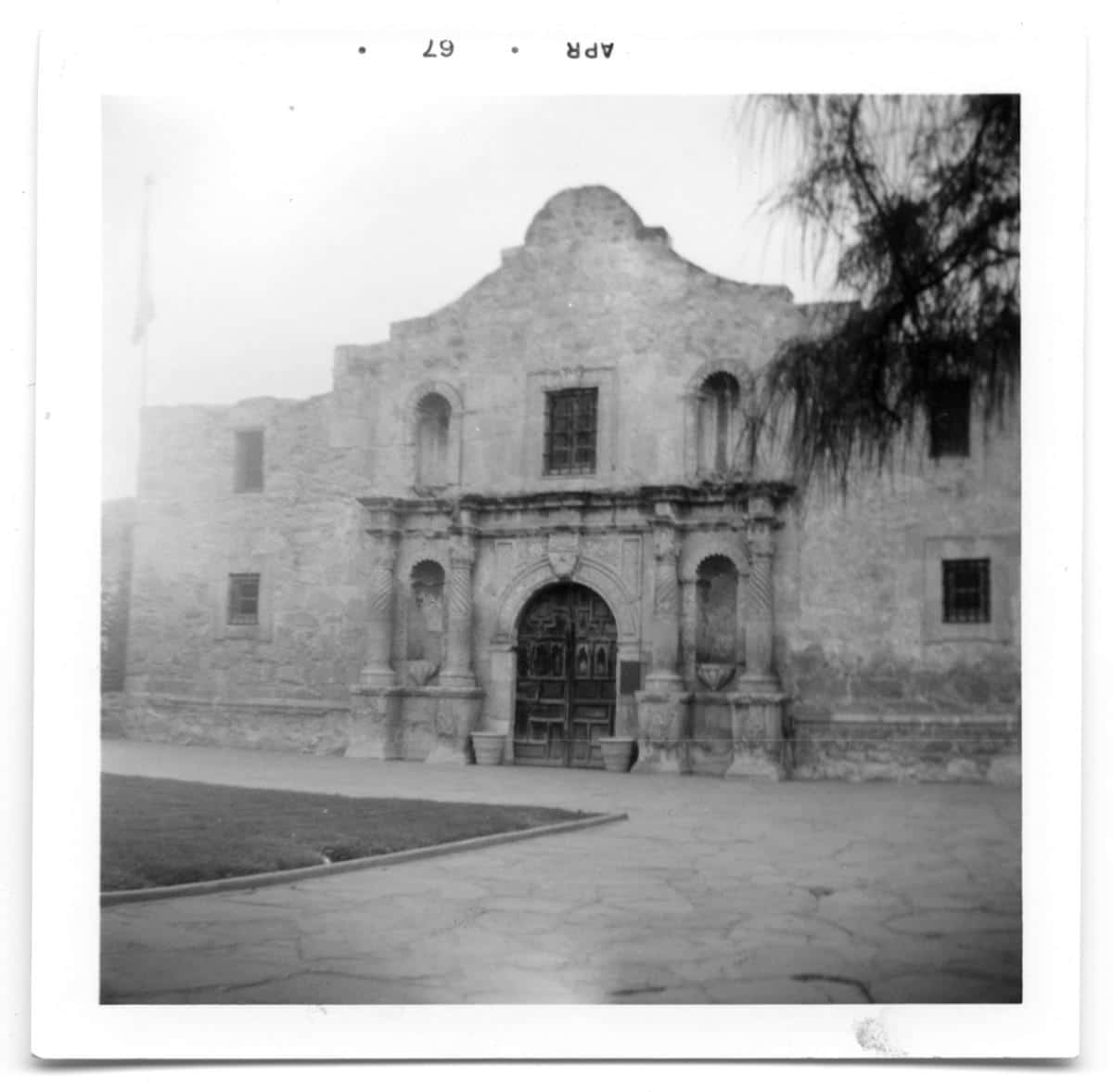

It’s an odd-looking set of buildings. A single story convento and a broken church (it was never a chapel) with a Moorish Taco-Bell façade that is recognizable globally. So much so that the humps have been copyrighted by the current management of the place. But in its plainness, there is beauty and some form of magnetism.

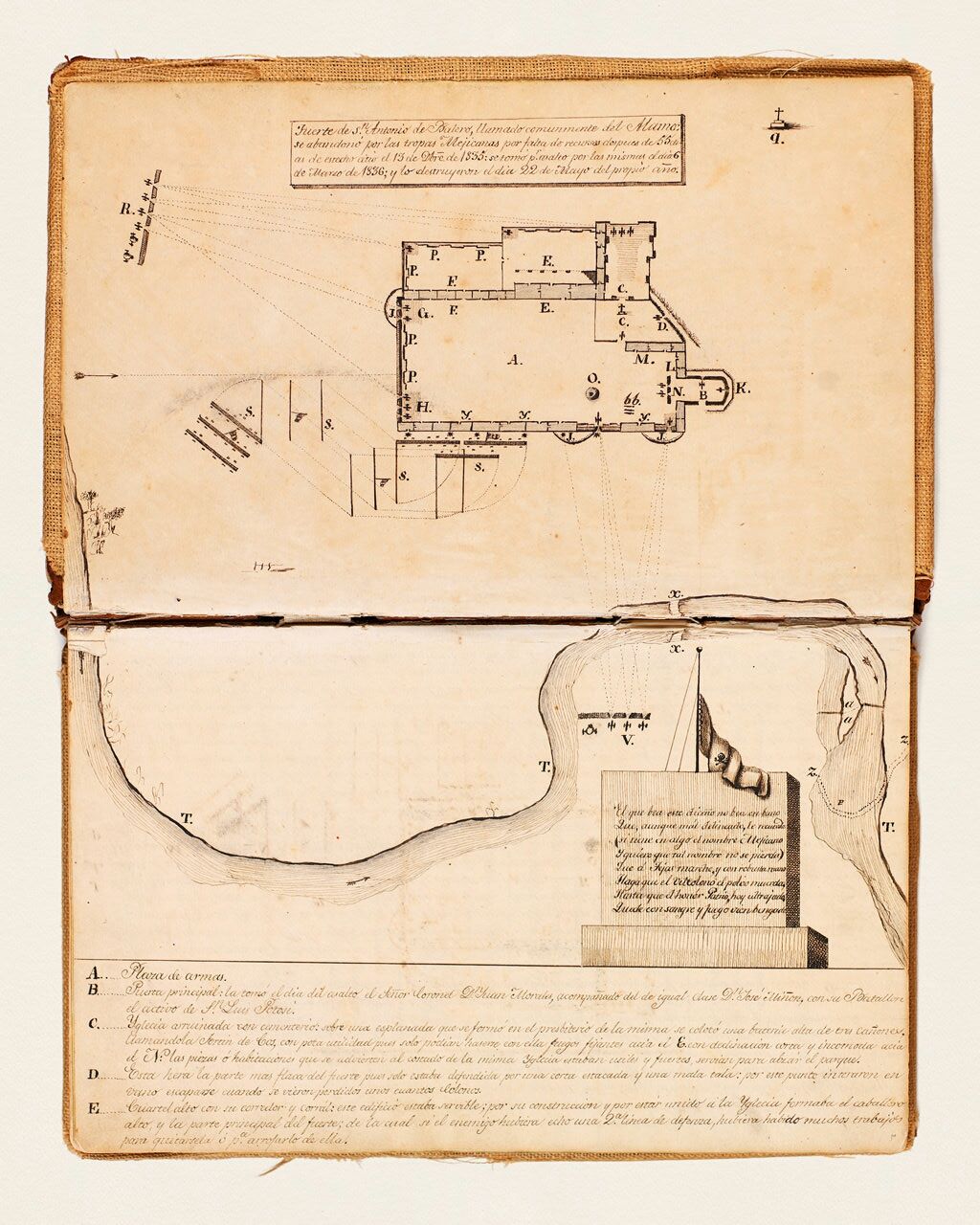

A tragedy occurred here, a sound defeat of the Texian and Tejano defenders courtesy of the soldados of President-General Antonio López de Santa Anna’s Division of the North. Shakespeare couldn’t have imagined it—the descendants of Germano-Celtic Protestants fighting the descendants of Iberio-Celtic Catholics. In a church, on a Sunday and before Mass.

The Alamo is not only history, it is Creation Myth, it is a religion. There are sacred texts, patriarchs, a Trinity, a Madonna and a Christ child. All overcoming a Lesser Satan in the almost anagram: Santa Anna. It also becomes a search for a Holy Land nestled within a David and Goliath framework with Texians and Tejanos garrisoned in their adobe and rock Tabernacle whilst other tribesmen drafted the new God-given Decalogue in Washington Town.

The Alamo is the Last Stand narrative. There are other Last Stands in history: the Hot Gates, Camarón, Wake Island, Masada, Khyber Pass and Saragarhi come to mind and each nation and people are justly proud of their particular sacrifice on the battlefield. But there’s a difference; with few exceptions these Last Stands were fought by professional soldiers who had the unity of esprit, training and duty to bind them. Not so with our Sad Stones of the Alamo where the defenders spake different languages, practiced different religions and had cultures and accents spreading from Rhode Island to the Río Guadalupe at least. Colonists of a decade or less mixed with native-born Tejanos who had no living family memory or experience outside of Texas, and Mexico was further away, in many ways, than the Thirteen Colonies were from Great Britain. The defenders had no commonalty of professionalism, certainly no martial discipline or esprit. The defenders’ connectivity was a reliance upon self, family and non-conformity to tyranny; in their minds, that was Duty and that was enough. Honor was a debt they owed their friends and family—their word. Sacrifice was the very cornerstone of the religion they’d been raised with and it was vital to their sense of self that, if ever cornered, not to back down.

And it is precisely that Duty and resistance to tyranny that Texans celebrate to this day and hopefully into tomorrow. Two years out of twelve of public education are devoted to Texas history, every school child daily Pledges Allegiance to Texas and we name our children Travis (and Austin); we debate endlessly The Line or Crockett’s Last Stand and accuse each other of not being true Texans (horrors!) if one disagrees with the other over such covenants and canon.

Now the Alamo is grudgingly marching into the 21st century and Texans cannot agree on whether to defend it as it is, or significantly recreate the 1836 footprint complete with restoration of buildings, cannon in battery, a gate and a world-class museum. Due to the unfortunate iconoclasm of our time where every statue and historical marker seems at risk, it’s no wonder so many Texans are rightly concerned with all this business to include the proposed movement of the Alamo Cenotaph approximately 500 feet south.

Did it matter?

Bowie to Travis – The Alamo (2004)

Why do Texans revere the Alamo and how does it relate to the identification of Texas and Texans? Gonzáles was not the hotbed of Anahuac or San Felipe; it was an example of moderation. Green DeWitt had even named the village, in 1825, for the then-governor of Coahuila y Texas. The colonists were determined to be good citizens of their new home. Even when their Sheriff Jesse McCoy was beaten by soldados there were no demands placed on Mexican authorities, other than asking for an apology.

Completing their organization and victualling for the journey, at about 2:00 pm on February 27, the Gonzáles Ranging Company of Mounted Volunteers of La Colonia de DeWitt de Coahuila y Texas de Republica Federal de México departed their homes, stock farms and cotton fields for the last time to answer Travis’ call. They had, in essence, “thrown themselves to the bears.”

When a call arrives, circumstances seemingly always provide reasons to excuse oneself—the crop is due, it’s hog killing time, my wife is expecting, Comanches, banditry, thievery and so on. (Banditry and thievery were indeed a most pressing concern Just the previous November, Courier Smithers had been badly beaten in Gonzales by recent volunteers from “the old states” while defending Susannah Dickenson and her infant daughter.) They had not received a new clarification message from Travis, yet the colonists adopted no “wait and see” attitude. How did they weigh the fear, the risk against the measure of Duty and Honor? They heard the call, saddled up and rode to the sound of the guns.

The example of Gonzales takes away all excuses – an expectant wife, a mother who is blind, teenage boys arguing with their fathers about who should stay and who should go. Those that were soon to become widows or childless encouraged their men to march to the Alamo. The oldest was 44 and the company included four teenagers.

Thirty-two filthy men on filthy horses had answered the call for reinforcements, the only known colony to do so. No generals or great captains rode with them and those in charge had merely been chosen as a first among equals. These men were freemen and not government hirelings set to a task.

They tried for hours in the dark and cold to locate the Alamo, but they were lost in the light mist and cloudy dark and could not determine one set of structures from another. It wasn’t rainy but the high humidity and near freezing temperature produced a dreadful discomfort—feet were unfeeling and thick inside the stirrups and those without gloves, and even those with, could barely control their reins and they were cloaked or coated against the terrible North Wind. Added to the physical misery of beasts and men was the frustration of being so near their destination, yet it was hidden to them and the thoughts of warming fires and blankets and the fear of Mexican Cavalry must’ve added to their emotions.

Soon, and strangely enough, an English (or Englishman) speaking man hailed them from beside the road and offered to escort them into the Alamo. They followed but only for a few moments when they detected perfidy and the escort galloped away into the night. They continued riding west and closer to the town when they hit the San Antonio River; a quick turn north and they discovered the Alamo.

Teenage boys are never going to die—even though they were surrounded by the accidents, epidemics and dreadful mortality of childbirth of that era. Andrew Kent argued with his son, David, about who was going to Bexar. The elder overruled the younger. But 16-year old William King won the argument with his pa, John King, and when he rode into the Alamo that morning, he had only five days to live.

Most of what people know about the Alamo is false and they rely on oral tradition more so than what is read. They remember the first things heard or movies they’ve seen and that becomes fact as surely as the Burning Bush. It’s frustrating but that is the power of oral history—it’s more important what Gospel one hears around a campfire than what one reads at night next to an oil lamp.

But what is consistent with both traditions are the virtues of Duty, Honor and Sacrifice.

Visit San Antonio

visitsanantonio.com

The Alamo Misión San Antonio de Valero

300 Alamo Plaza

San Antonio, TX 78205

(210) 225-1391

thealamo.org

Hours/Admission

The Alamo Church, gift shop, and grounds are open to the public from 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. daily. To visit the inside of the Alamo Church, visitors will need to claim a free timed ticket.