Early in 1869 an intense manhunt closed in on Cullen Montgomery Baker, a vicious desperado of early Texas. Although born in Tennessee, Cullen moved with his family to Cass County, Texas, in 1839 when he was four. Cullen grew up hot-tempered and quarrelsome, and he became a heavy drinker while still in his teens.

When he was nineteen, in 1854, Baker killed his first man, and two years later he claimed his second victim. In 1861 he enlisted in a Confederate cavalry troop in Cass County. But Baker soon deserted, joined the Union army, then deserted again and united with a gang of bandit raiders.

After the war, Baker organized a band of thieves and, after a number of murderous depredations, he was pursued by both bounty hunters (a $1,000 reward was on his head) and U.S. soldiers. Baker and a gang member, “Dummy” Kirby, took refuge in a private home in Bloomburg in East Texas. On January 6, 1869, Baker and Kirby were killed with several bullets apiece and, it was rumored, with strychnine in their whisky. On Baker’s corpse were found a shotgun, four revolvers, three derringers, and six pocketknives. The bodies of the two outlaws were dragged through the streets of Bloomburg.

By the time Cullen Baker was slain, another homicidal young Texan was making his bloody mark on the annals of outlawry in the Lone Star State. John Wesley Hardin was born in 1853 in Bonham, the son of a circuit-riding Methodist minister. Although named after the founder of Methodism, at the age of eleven John Wesley stabbed another boy twice in a knife fight.

During the Civil War Wes took target practice at an effigy of Abraham Lincoln. When he was fifteen, in 1868, he pumped three pistol slugs into a former slave near Moscow in East Texas. Pursued by a trio of Reconstruction soldiers, Wes set an ambush near a creek crossing. He shot gunned two of the soldiers and killed the third trooper with a .44 revolver. Several ex-Confederates concealed the corpses while Wes, wounded in the arm, fled the scene.

The young fugitive began to drink and gamble, and there were other shootings. Arrested near Marshall in 1871, he shot a guard and escaped. Soon he left the state with a cattle drive, but after reaching Kansas he killed two more men.

Back in Texas in 1872, Hardin wounded members of the State Police in two separate incidents. In 1873 in Cuero, Hardin murdered a deputy sheriff, and later in the year he killed Sheriff Jack Helm. The next year Hardin celebrated his twenty-first birthday in Comanche. During an exchange of shots with Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb, Hardin was wounded in the side, but he drilled the lawman in the head. Hardin fled town ahead of an enraged mob, but his brother Joe and two other companions were captured and lynched.

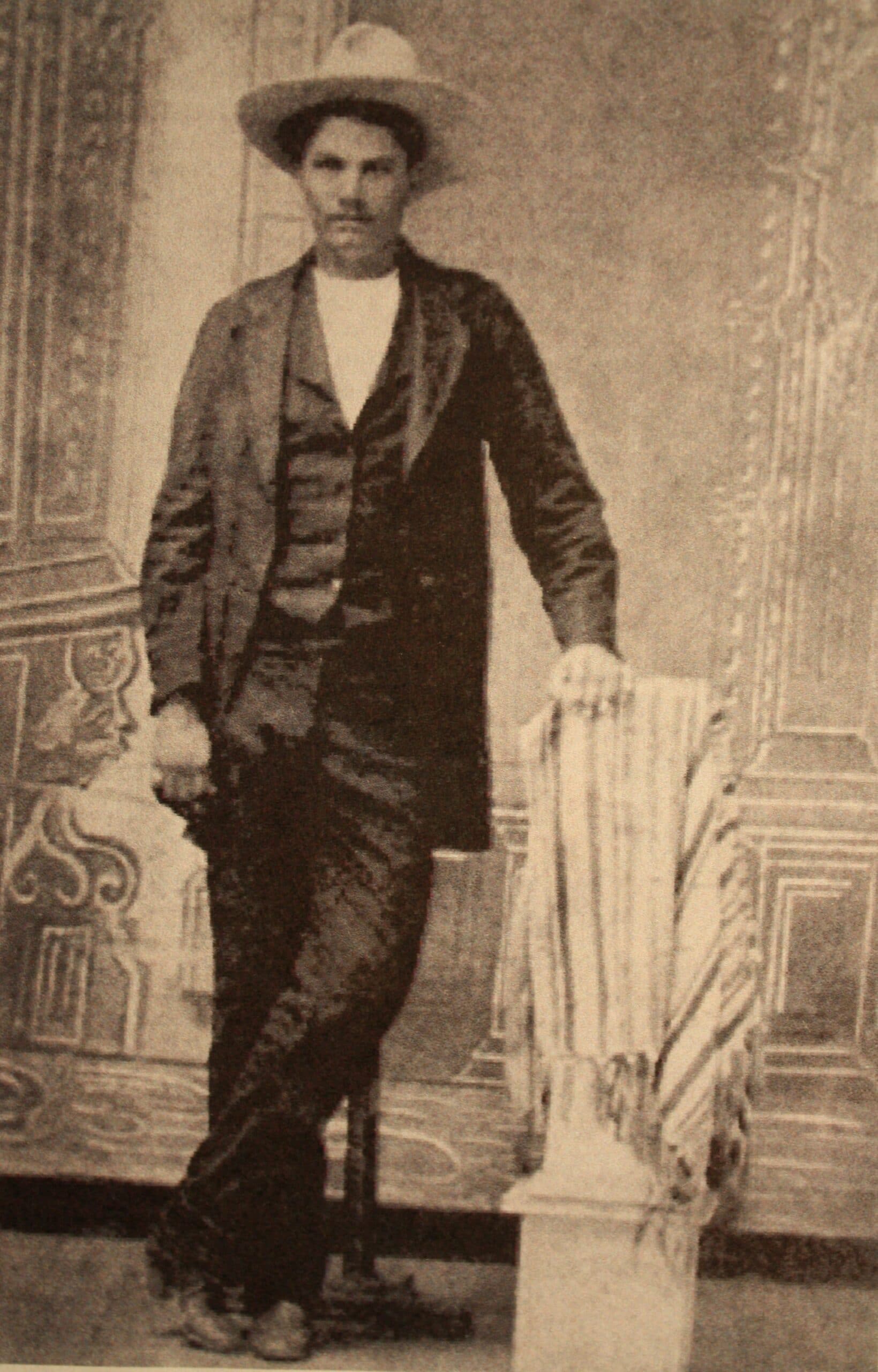

John Welsey Hardin (right). Author’s collection

The State of Texas posted a $4,000 dead-or-alive reward on the head of John Wesley Hardin. The fugitive, with his wife and small children, relocated to Florida, and for three years Hardin lived quietly as “J.H. Swain Jr.” But in 1877 Texas Ranger John B. Armstrong tracked Hardin to a passenger train in Pensacola. Hardin’s companion triggered a shot that punched a hole in the Ranger’s hat, but Armstrong shot him in the heart. Hardin reached inside his coat for a long-barreled Colt .45, but the gun caught in his suspenders. Armstrong pistol-whipped and handcuffed his prey, then whisked him by train back to Texas, where Hardin was sentenced to the penitentiary in Huntsville.

After more than sixteen years of incarceration, Hardin was released in 1894. His long-suffering wife, Jane, had died before he left prison, and Hardin soon married a young girl who left him on the day of their wedding.

Hardin gravitated to El Paso, where he drank heavily and ran with a hard crowd in the notorious border town. He vehemently clashed with John Selman and John Selman Jr., both peace officers in El Paso. Old John, formerly a rustler but now a city constable, burst into the Acme Saloon on the evening of August 19, 1895.

Constable Selman fired a pistol shot into the back of Hardin’s head, then shot him twice more when he collapsed onto the floor. At forty-two Hardin was buried at Concordia Cemetery. The following year Selman was shot to death by fellow lawman George Scarborough, and Old John also was interred at Concordia.

An outlaw contemporary of Hardin’s was Bloody Bill Longley. Longley was born in Austin County in 1851, and he spent a large part of his boyhood learning to shoot. Bloody Bill murdered Wilson Anderson for killing a relative. Longley next murdered Reverend William Lay, who was milking a cow. He killed Lou Shroyer in a running fight, and two other victims brought his total to five by 1877.

Now a wanted man, Longley fled to western Louisiana, where he rented land near Keatchie. Two lawmen from Nacogdoches slipped into Louisiana and, at shotgun point, “extradited” Longley back to Texas. Jailed in Giddings under a death sentence, Longley complained to the state government that his punishment was unjust because Wes Hardin had received merely a long prison term.

While fruitlessly awaiting appeal action, Longley spent his time writing long, pious letters of regret to various newspapers. When Bloody Bill finally was executed, five days short of his twenty-seventh birthday in 1878, he plunged to the ground because of a defective noose and had to be hoisted up and rehanged.

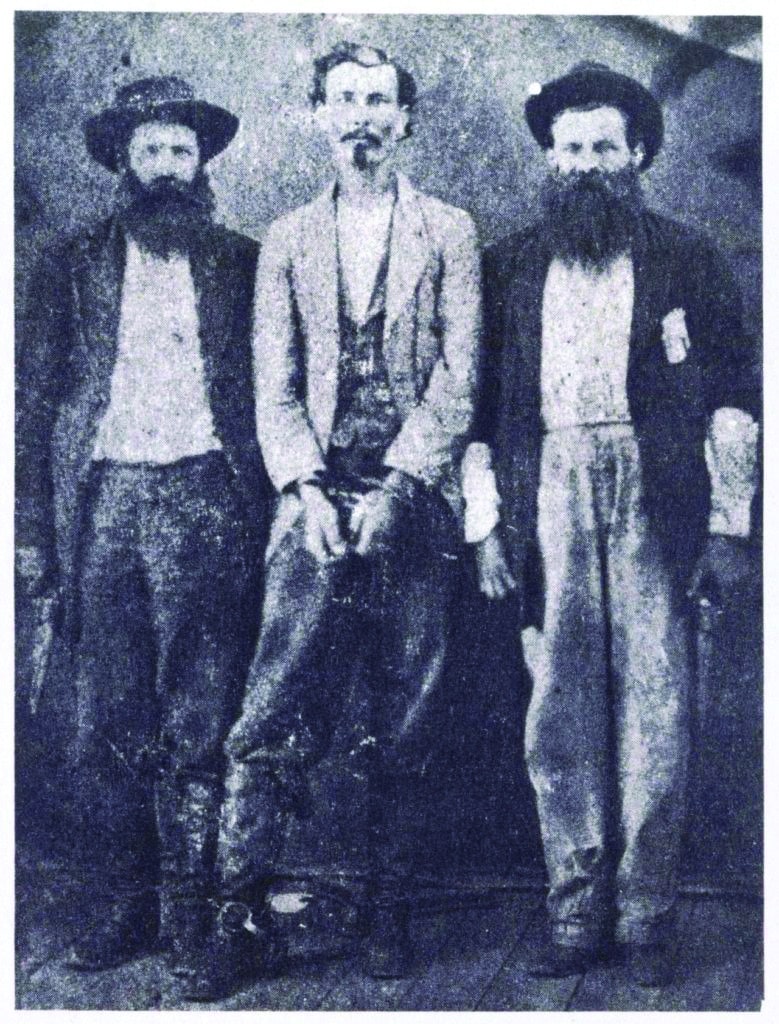

Bloody Bill Longley (middle) just before his execution. Author’s collection

Like Bloody Bill Longley, Sam Bass both was born in 1851 and he met his end at the hands of the law in 1878. Although born in Indiana, Bass was orphaned during childhood and reared by an uncle. At nineteen the rootless young man turned up in Denton, Texas, and he hired on as a farmhand for Sheriff W.F. Eagan.

In 1876 Bass and Joel Collins led a herd of cattle to booming Deadwood in Dakota Territory. Bass and Collins soon turned to crime, enlisting a few eager desperadoes and looting several stagecoaches in the Black Hills. In 1877 Bass and his henchmen robbed a train in Nebraska of $65,000, but within several days Collins and two other outlaws were hunted down and killed.

Bass fled to Texas and organized another gang. In the spring of 1878, the Sam Bass Gang staged four train robberies in the Dallas area. Even though the robbers garnered little loot, a widespread manhunt was launched.

Bass next intended to rob a bank in Round Rock, but gang member Jim Murphy betrayed the plan to Texas Rangers in return for leniency. Round Rock, therefore, was teeming with lawmen on Friday afternoon, July 19, when Bass led Jim Murphy, Seaborn Barnes, and Frank Jackson from their camp to case the town one more time before holding up the bank on Saturday. But Murphy prudently dropped behind his companions, muttering something about his horse.

Bass, Barnes, and Jackson entered a store, where they were accosted by two suspicious deputy sheriffs. The outlaws gunned down both officers and bolted for their horses. Texas Rangers and several citizens opened fire, and Barnes was killed by Ranger Dick Ware. Bass and Jackson galloped away, but Ranger George Harrell sent a slug through Sam’s torso. The two outlaws escaped into the growing darkness, but Bass could not stay on his horse. Jackson rode on and escaped, while Bass was found on Saturday and died on Sunday – his twenty-seventh birthday.

(Left) Sam Bass was buried in the cemetery west of Round Rock. Photo by the author

Destined to become the West’s premier assassin, Jim Miller was one year old in 1867 when he moved with his family to Texas from Arkansas. After the boy was orphaned, he was sent to live with his grandparents in Evant. When Jim was eight his grandparents were murdered in their home. The boy was arrested but never charged, then released to live with a married sister near Gatesville. But the hot-tempered youngster clashed with his brother-in-law, and Jim shot him while he slept, setting the pattern for the rest of his life.

By the 1890s Jim “Killer” Miller was known as a murderer for hire, often riding great distances following a homicide to establish an alibi. An expert gunman, Miller sometimes found employment as a lawman. In Pecos he wore the badges of city marshal and deputy sheriff, but in 1894 he feuded with Sheriff Bud Frazer.

Frazer twice opened fire on Miller in the street, but “Killin’ Jim survived both assaults and Bud fled to New Mexico. In 1896 Frazer returned to the area, but Miller found him in a Toyah saloon, blasting away most of his face with a shotgun. When Bud’s sister cursed the murderer, Miller threatened to shoot her too.

In 1899 Miller ambushed and killed Joe Earp, who had testified against him during a trial. It took four bullets to finish Lubbock lawyer James Jarrott. “He was the hardest damn man to kill I ever tackled,” admired Killin’ Jim. In 1904 Miller murdered Frank Fore in a Fort Worth hotel, and two years later he killed lawman Ben Collins. Little wonder that when Pat Garrett was bushwhacked in 1908, widespread blame was placed on Killer Miller.

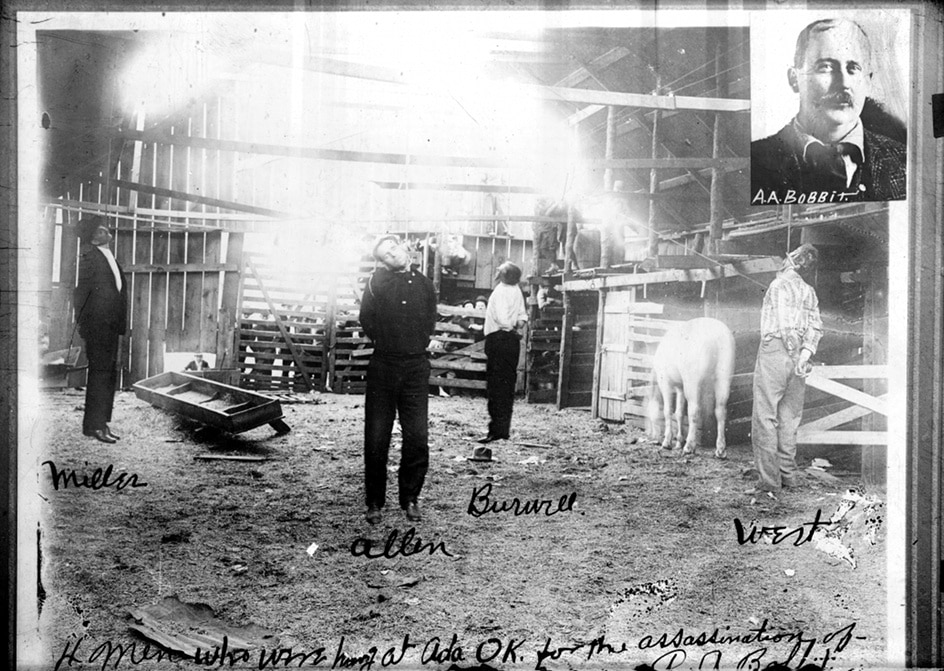

In 1909 Miller was hired to kill Gus Bobbitt, a rancher near Ada, Oklahoma. Killin’ Jim emptied both barrels of a shotgun into Babbitt outside his home, but when he returned to Fort Worth, where his wife owned a boarding house, he was arrested. Texas officials eagerly extradited him to Oklahoma, where he was lynched alongside his three employers.

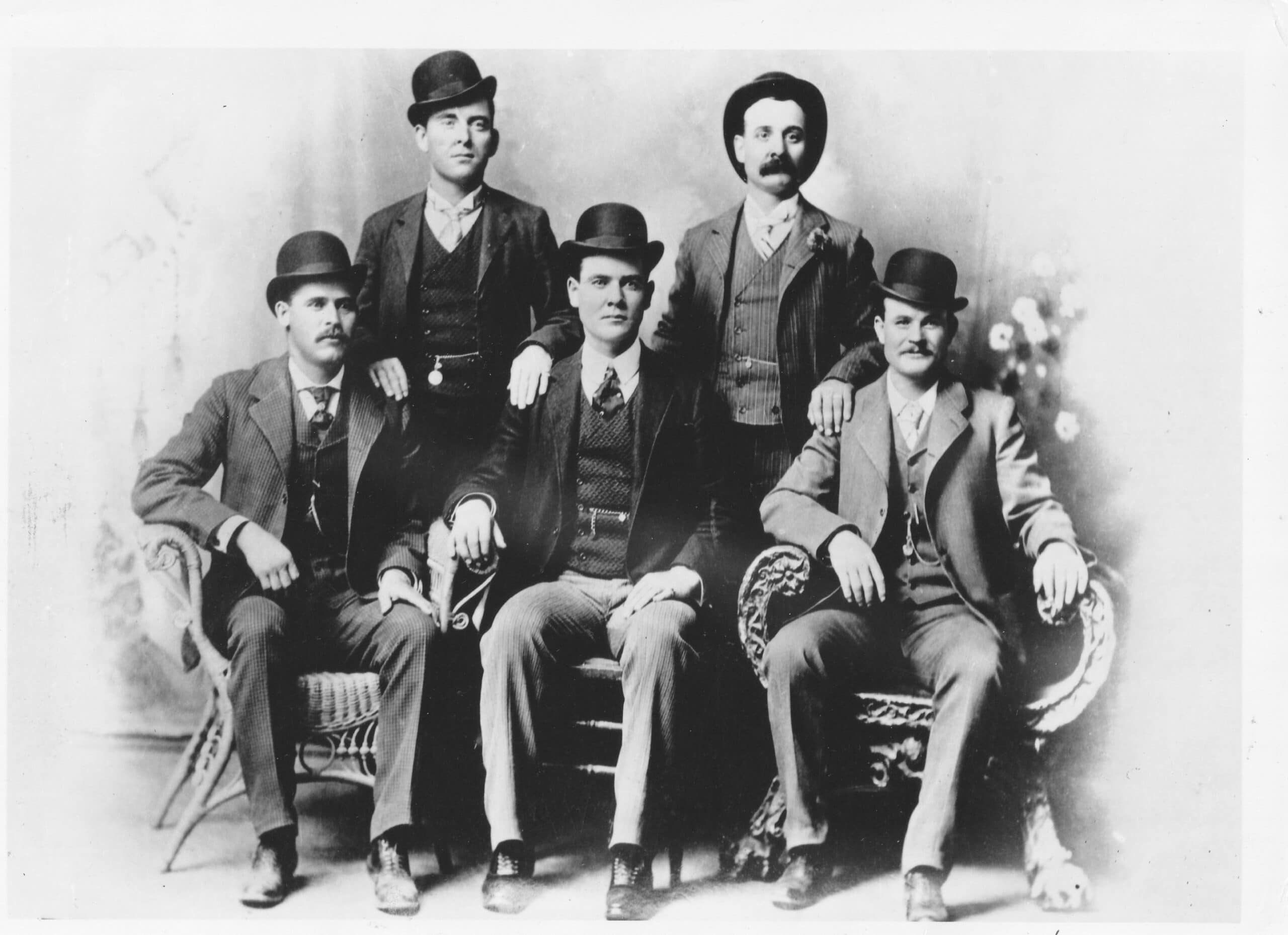

Even outlaws who operated in other parts of the West liked to vacation in Texas. Rustlers who followed the Outlaw Trail, which stretched from Canada to Mexico, sold stolen horses in El Paso to Mexican ranchers, then caroused in Tillie Howard’s sporting house and other dives. And in 1900 Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch vacationed in Hell’s Half Acre in Fort Worth, where they posed for a famous photograph. For outlaws of the West’s horseback era, Texas was the place to be.