“Come here, I want to show you something”

Ray Benson walks into his office and points to a framed picture on the wall, a poster-size print of the photograph on the cover of For the Last Time, the last record Bob Wills appeared on. On December 3, 1973, several Texas Playboys, joined by Merle Haggard, reunited in the studio and insisted that Wills be there.

Four years earlier, a stroke had robbed Wills of the ability to play his fiddle or sing. That night, he’d suffer another stroke. Though he lived another 18 months, he never spoke again.

“That’s the last picture of Bob Wills alive,” Benson says. “He was sitting there in a wheelchair, and that’s when I met him. That’s a man who’s about to have a stroke.

Now, look at those eyes.”

The Bandleader

For some, whether Wills is the Father as well as the King of Western swing makes for a lively debate. Writer Cary Ginell gives credit for paternity to Milton Brown, who sang with Wills from 1930 to 1932 in the Light Crust Doughboys, created the Musical Brownies a year before Wills founded his own band, and died at 32 in a car crash in 1936. Brown’s music does bear a strong resem- blance to that of the Playboys. Apart from adding drums and jazz instruments, what did Wills bring to Western swing?

“Charisma,” says Benson. “Total, absolutely incredible, ridiculous, outrageous charisma. Pierre Cossette produced the Grammy Awards for 20 years … before that he worked with Frank Sinatra, Ann-Margret, others like that … and he told me that Bob Wills had more charisma than anyone he’d ever worked with. He said that when Wills stepped onstage, it was like a light bulb” — Benson mimes pulling a bulb’s string — “and every musician I ever talked to said the same thing. He’d look at you with — they called it ‘these burning black eyes’ — his eyebrows would come down. Man, he was turned on.”

In his autobiography, Willie Nelson describes the first time he saw Wills perform in 1946, when Nelson was 13: “He was almost like an animation. Watching him move around, I thought: This guy ain’t real. He had a presence about him. He had an aura so strong it just stunned people. You had to see him in person to understand his magnetic pull. John the Baptist had the same pull.”

Those who played with him struggle to convey what the Welsh country-punk musician Jon Langford calls the man’s majesty. Bassist Louise Rowe, the only female instrumentalist Wills ever hired, joined the Playboys in 1952. “He was the best bandleader ever,” she says. “Unbelievable. He pulled out of you whatever music you had inside of you. Any Playboy will tell you that when Bob looked at you with those brown-black eyes and pointed that fiddle at you, you did the very best you were able to do. I don’t feel as though I’m as good as any of those Texas Playboys, but he got my best, and the best of everyone else.”

Leon Rausch, who became the voice of the Texas Playboys in 1958, is still at a loss to explain his boss’s powers. “No one could ever figure out what the magic was about Bob,” Rausch explains. “He’d show up late sometimes, and we’d be playing and just look at each other. We could tell when the old man would hit the building. We didn’t even have to look out to see if he was there, but the band would start coming up just a little bit tighter. I know that sounds weird. He had a magic about him.”

With his slippery, jazz-based solos and pioneering electric guitar work — in 1974 Rolling Stone called him the world’s greatest rhythm guitarist — Eldon Shamblin played with Wills from 1937 to 1954 and was as responsible as anyone in the band for shaping the sound of Western swing. In the mid-1990s he tried to explain Wills’ dynamism to writer Duncan McLean. Those who weren’t dancing, Shamblin said, “would stand 30 deep out in front of the bandstand, from maybe 15 minutes before we started playing; and they’d stand there for four hours and never move. He just hypnotized them people.”

1951’s Snader Telescriptions — filmed performances made for later broadcast on television and now available on YouTube — provide a sense of what Benson, Rowe, Rausch and Shamblin are talking about. Take “Ida Red,” which shows Wills and his band at full throttle. There’s an almost unnerving electricity, a pres- ence that’s almost too hot, too earnest. When he plays, Wills stands ramrod straight but mobile, shoulders back, fiddle either at full mast or weaving — Hot Club of Cowtown’s Elana James tells her fiddle students to hold their bodies and fiddles like Wills — and when he doesn’t, he holds his arms out, welcoming us in, or he conducts the band with his bow and his free hand, calling out the soloists by name, directing that famous gaze at each in turn, like a spotlight at close range.

Seventy years on, that lack of ironic distance can be alienating for some, but not all. “Maybe that’s what I like about Wills,” says James. “There was no filter. And maybe that’s why Western swing isn’t more popu- lar. It’s an unironic genre. You can’t do it justice by getting on stage in flip-flops and a t-shirt and shoe-gazing or by being pretentious or ironic. It’s the opposite of all those things. You’ve got to be all in.”

The most recognizable badge of Wills’ uninhibited commitment is his holler. Asked what Wills brought to the music that Milton Brown hadn’t, Gimble fires back: “Ah haa!” It quickly became his signature, and those most in thrall to Wills today, including Ray Benson and Asleep at the Wheel, carry on the tradition. But it wasn’t always greeted so warmly.

At the Playboys’ first recording session in 1935 with American Record Corporation’s British-born producer Art Satherley, Wills hollered, whooped, jived and called out soloists’ names as the band burned through “Osage Stomp” and “Get With It.” One would think that a band mak- ing its first record with a major label would try to clean up their rough-around-the-edges dance hall demeanor, but that wasn’t how Wills operated. Satherley had never heard anything like it, and in the middle of “Get With It,” he cut the band off.

“Bob, you’re going to have to hold it down some,” Satherley admonished. “When you talk, you’re covering up the musicians.” Writer Rich Kienzle relates what came next.

“Is that right?” Wills, then 30, had a quick temper and a stiff spine. He turned to the band. “Pack up, we’re going home.”

Satherley tried to recover. “No, Bob, I don’t want you to go home. I want you to make records for us!”

“You hired Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, and Bob Wills hollers any- time he feels like it and says whatever he wants to say! Now if you want to accept that, Mr. Satherley, we’ll do it. But if you don’t, we’re goin’ home.” The band stayed, and Bob kept hollering.

Some still find Wills’ jive an irritating distraction. In his two thick volumes of jazz commentary, Visions of Jazz and Weather Bird, the great critic Gary Giddins mentions Wills exactly three times, and each time it’s for the “annoying falsetto cries” that Giddens believed ruined otherwise decent Big Band charts.

Can even those in the front pews of the Church of Bob admit that sometimes they are a distraction? It would be a minor miracle if they never obtruded a little awkwardly, decades later, on the music. After all, they’re ecstatic exclamations of one man’s private pleasure. “Some of those ‘Ah haas,’” drummer Dacus told Townsend, “you’d swear never came out of a human.” Wills said that his hollers and jive came from two boyhood sources: ranch dances in West Texas, where his fiddle-playing father and the cowboys in the crowd would cry out when the music or whiskey moved them, and the banter of black musicians he played with as a boy. That uninhibited spirit, the playful freedom he took in music, was with him from the start; it wasn’t an affectation, though the chatter can sound like it to anyone who can’t get on Bob’s wavelength. And sometimes the wavelength is way left of the dial. At those times, it’s like listening to a believer speaking in tongues: the congregants hear the inspiration but don’t always share it.

What the hollers speak to above all is that this is soul music. “Bob played things the way he felt,” says Townsend, whose 1976 biography, along with Rich Kienzle’s book-length liner notes for two magisterial Bear Family collections of Wills’ music, remains indispensable. “I asked Leon [McAuliffe, the first of many great steel guitar players in the Texas Playboys], what made his music so appealing? He said it was Bob’s soul. He said they’ve all tried to copy it, and he left enough recorded music for others to play like he did. They could copy his music, but they couldn’t copy his soul.” And part of what made not only Wills’ music but Wills himself so appealing during the darkest years of the 20th century was the man’s roots.

1905–1934

From Turkey to Tulsa

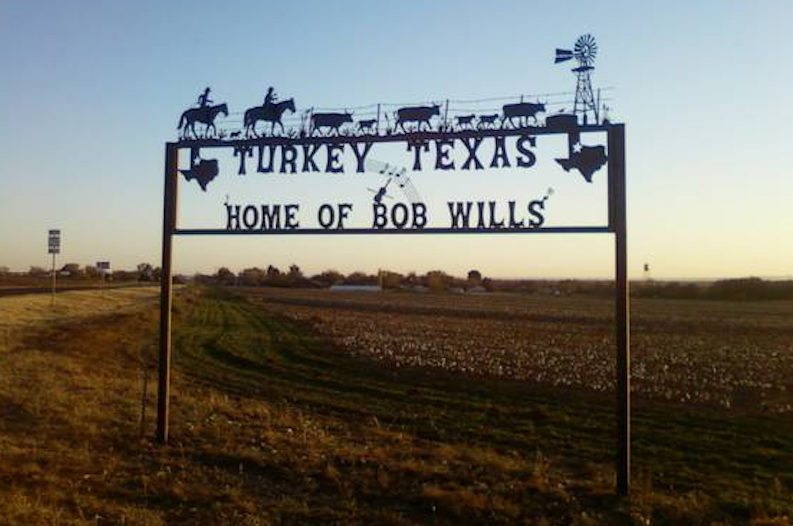

James Robert Wills was born in 1905 in Limestone County in east-central Texas, the first of 10 children born to dirt-poor cotton farmers. There was Cherokee blood on his mother’s side and a wealth of fiddlers on both, including his own father, John, who wasn’t much of a farmer but was known throughout the region for his breakdown fiddling. When Bob was 8, the extended family left their farm and set off on a two- month, 500-mile journey north- west to the Red River Valley near Turkey, stopping along the way to pick cotton and play music. The farming continued as hard as ever, and John kept the family fed playing dances, with young Jim Rob accompanying him on man- dolin. One night, after his father had sent him ahead to a dance, the 10-year-old was pressed into service on fiddle when John got drunk instead and didn’t show up until the dance’s end. Jim Rob played the six songs he knew on fiddle and kept on repeating them, which mollified the dancers and whetted Jim Rob’s enthusiasm for the instrument.

Jim Rob dropped out of school after the seventh grade to work full-time on the farm, working alongside black laborers and learning their music. At night, he’d play dances late into the night with his father, mostly accompanying him on mandolin. As a teenager he learned long- bow fiddling technique from his grandfather and pop tunes from a trained violinist who played dances in the area, and he was beginning to step out on fiddle solos alongside his father when he decided at 17 to chuck the farm and set out on an eastbound train, looking for work that was less hardscrabble and left more time for music.

Over the next five years he held a series of dead-end jobs, got drunk, raised hell and fiddled. He also fell in love with the blues music of Bessie Smith, whose singing, he told Townsend 50 years later, was the best thing he’d ever heard then or since. He married the first of five wives when he was 21 and decided to take up barbering because, unlike farming, it wouldn’t destroy his left hand for fiddling. The newlyweds moved to Roy, New Mexico, where he learned Mexican music and occasionally adapted his own playing to suit the kinds of dances the local Mexicans liked.

After returning to Turkey and spending a night in jail for rowdiness, he lit out for the wilds of Fort Worth, which is where his musical career proper began. There he connected with guitarist Herman Arnspiger and singer Milton Brown, with whom he formed first the Wills Fiddle Band in 1930, then the Aladdin Laddies and finally the Light Crust Doughboys — sponsored by Burrus Mills, maker of Light Crust Flour and managed by eventual Texas Governor, U.S. Senator and world- class scoundrel Pappy O’Daniel. In 1931, with O’Daniel as emcee, the Doughboys began broadcasting on radio, and in 1932 they recorded two songs, “Sunbonnet Sue” and “Nancy Jane,” that were somewhere between traditional fiddle music and what would become Western swing. It’s the only time Wills and Brown ever recorded together. Later that year, Brown, fed up with O’Daniel’s prohibition of side gigs, quit and formed his own band, the Musical Brownies, a string band that played the jazz- based pop music of the time and left room for improvisation, like a jazz band. The Brownies were still going strong when Brown died in 1936.

Wills himself got sick of O’Daniel’s tight-fisted ways and quit the Doughboys in 1933. He persuaded fellow Doughboys Tommy Duncan and Kermit Whalin to come with him to Waco, where they joined Bob’s brother Johnnie Lee and Whalin’s brother June and began hosting a radio show, calling themselves the Texas Playboys. They followed Brown’s lead and played the popular dance tunes of the time, but the band was unpolished. Because they had the temerity to describe themselves on posters as “formerly of the Light Crust Doughboys,” O’Daniel sued and won an injunction in McClennan County. To escape the long arm of O’Daniel, and also to find a territory where Milton Brown wasn’t already entrenched, the band fled to Oklahoma in 1934, where they eventually found a radio home at KVOO in Tulsa.

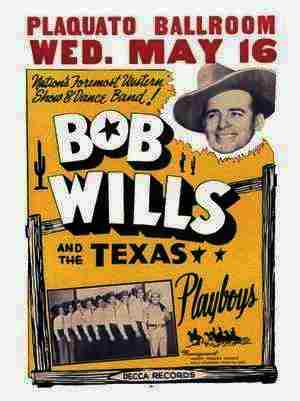

Much of the value in radio for bands in the 1930s came as advertising for their own dance shows, and if they could find a sponsor who’d pay for airtime in exchange for dropping the com- pany’s name in front of their music, so much the better. Wills found both in Tulsa when his man- ager, Oliver W. Mayo, set up a regional dance circuit that got regular promotion on KVOO and located a willing sponsor in the laxative Crazy Water Crystals, which paid for a six-days-a-week half-hour radio show at 12:30 p.m. Wills was on his way.

1935–1950

Tulsa to Hollywood

Cain’s Dancing Academy in Tulsa, where Wills began broadcasting Thursday and Saturday night shows every week, was a large converted garage with a maple dance floor. Townsend, who first visited Cain’s in the late 1940s, remembers it well: “They had big old car springs under the floor, which is why it was so wonderful to dance there.”

Wills began to turn his attention to refining his band. He’d admired the Brownies’ Bob Dunn, an innovative electric steel guitarist, and Wills’ bandmates told him about a Dunn protégé, Leon McAuliffe, who was playing with O’Daniel’s Light Crust Doughboys. Wills poached him, and then another Doughboy, fiddler Jesse Ashlock, and next persuaded stride pianist Al Stricklin to leave Fort Worth for Tulsa. With a formidable string ensemble in place, Wills began assembling the pieces that would take the music to places it had never been.

A fan of the popular big jazz bands of the time, Wills added a trumpet, a saxophone and a trombone to his string outfit, and then drummer Dacus, who inaugurated the era of Wills’ signature big beat. The 13-man lineup consisted of two fiddles, two guitars, steel guitar, tenor banjo, bass, piano, trumpet, trombone, saxophone, drums and vocalist Tommy Duncan, who also played guitar. Wills cut 26 sides with American Record Corporation in 1935, 35 in 1936, and 33 in 1937 before guitarist Eldon Shamblin joined the band later in 1937. Shamblin is a pivotal figure: a jazz musician, he was among the earliest to make the electric guitar a frontline solo instrument as well as part of the rhythm section. He also brought a new level of sophistication to the band, arranging dense Big Band charts and developing what would become a staple Playboys sound, twinning his guitar runs with Leon McAuliffe’s steel guitar.

By 1940, Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys were the biggest band in the Southwest and California, and Wills was one of the biggest celebrities in the region. Their repertoire mixed covers of blues, jazz and pop tunes with originals, many of them built on the bones of old folk melodies. However, little of the fame translated east of the Mississippi, despite the national success of “New San Antonio Rose,” his biggest-selling record to that point. In the early 1940s Wills made 13 full-length Hollywood movies, singing and acting (gamely) in what he called, self-mockingly, “seven-day wonders,” since they took about that long to make. Benson prizes a 1941 Go West, Young Lady poster that was distributed throughout the Southwest. The movie starred Ann Miller, Glenn Ford and Penny Singleton, major stars at the time, and in the posters sent to most of the country’s theaters, their faces were featured prominently, while the tagline “with Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys” was buried in a smallish font below the title. But on the poster distributed in the Southwest, the three stars got the sub-titular credit, upstaged by an enormous and solitary headshot of the grinning Wills looming over everything.

Despite his cowboy hat and rural roots, Wills’ use of horns, drums and electric guitars, as well as his eclectic choice of material, made him a queer fish to country music’s gatekeepers. He wasn’t currying favor with them, either. “Please don’t con- fuse us with none of them hillbilly outfits,” he told TIME in 1945. Nevertheless, on Dec. 30, 1944, Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry begrudgingly opened its doors to Wills and hisband. Not wanting any citified instruments to bespoil their stage, Opry officials insisted that drummer Monte Mountjoy be segregated behind a curtain from the rest of the band. Roy Acuff was getting ready to introduce the group, which was still setting up behind the main curtain, when Wills found out. He was livid. “Move those things out on the stage,” he demanded.

Band members helped Mountjoy hustle his kit out front, and when the curtain was drawn, the group tore into “New San Antonio Rose.” “The crowd screamed and carried on the way they did over Elvis Presley years later,” Minnie Pearl remembered. Incensed, the Opry wouldn’t let them play an encore.

By this time, Wills was the recognized king of what was now called Western swing. The band sold out dance halls throughout the Southwest and on the West Coast and recorded a score of hits. In 1947, hoping to cut back on the touring, Wills moved his base of operations from Tulsa to Sacramento, bought and restored a local ballroom, and arranged for daily radio broadcasts. But the dance hall soon became a financial burden, and Wills’ drinking, which had sporadically caused problems before, became worse. He began to miss shows. After overhearing Tommy Duncan grumble about it, he fired him in 1948. Herb Remington, who’d joined the band two years earlier, remembers the conflict. “The hard thing was that Tommy had to cover for him too many times,” Remington says. “When Bob was on the bandstand, he could sell any tune. But he was no angel.”

In 1949, Wills moved to Oklahoma City, and in 1950 to Dallas, where he opened a lavish new ballroom called the Bob Wills Ranch House. He also charted one of his biggest hits, “Faded Love,” an old fiddle tune slowed to a ballad, with lyrics added by Bob’s brother, Billy Jack. But times were about to change.

1951-1969

The Twilight of the Dance Halls

Television changed everything. According to Townsend, “The people who were once the great dancers got older, and when tele- vision came along, they stayed home. That was the end of a great age. Bob survived, whereas the other big bands didn’t, because he used fiddles and guitars, and country music had become popular and people associated him with it. Bob didn’t like the label, but the best thing that ever happened to him was his being labeled country music.”

Wills was also facing new competition from younger country singers from Nashville, including an upstart named Hank Williams. Remington remembers the first time he heard Williams sing “Lovesick Blues.” “I thought it was the awfullest thing I’d ever heard,” Remington says. “I mean, here we were, the Texas Playboys, and we were wondering, How did the people who came to our dances go from Western swing to Hank Williams? What did they hear in that guy? They loved him. I couldn’t get over that. But I finally got it.”

As financial woes forced Wills to sell the Ranch House in 1952 and, eventually, much of his song catalog, his binge drinking returned. Western swing’s popularity continued to slide with the arrival of Elvis Presley and rock ’n’ roll. Unlike many established stars, Wills saw Presley as another link in the great chain of rhythm-based music. Leon Rausch remembers that Wills was “fascinated by Elvis, but he didn’t talk about him much. Bob was into dance music. He didn’t think show people like Elvis were any threat to him, but he was wrong. Of course, Elvis was a great fan of Bob’s.”

Wills returned to Tulsa in 1958, and a 1960-62 reunion with Tommy Duncan reignited some interest, but the days of the Big Bands and Western swing’s heyday were long past. He recorded a few albums with Kapp Records in Nashville during the 1960s but met with about as much luck and understanding there as that other Texas renegade and Wills fan, Willie Nelson.

In 1969, one year after being inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame and a day after being honored in both houses of the Texas State Legislature, Wills suffered a major stroke that ended his playing career and impaired his speech. His memory, however, was unaffected, which became a godsend when Townsend, then a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, conceived the idea of making Wills the subject of a serious biography. He would interview him dozens of times in Wills’ Fort Worth home over the next four years.

1970-75

The Resurgence

Merle Haggard had seen Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys many times during his youth in Bakersfield, Calif., and had remained a fan. After Wills’ stroke, he decided to learn the fiddle, bring together several ex-Playboys with his band the Strangers, and put out an album of Wills standards, Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World. Western swing was back on the map.

Haggard arranged several benefits for Wills over the next three years, and in fall 1973 planned a two-day recording session that would reunite Wills with the Playboys. Townsend, whose liner notes for For the Last Time would win a Grammy, was there — he takes the part of emcee on the album, announcing that “The Texas Playboys are on the air” — as were Ray Benson and the original members of Asleep at the Wheel. On the first day of recording, Wills sat in his wheelchair with the band in a semicircle around him. When he wanted to hear a soloist, he would point at them, just as he’d done with his bow years earlier. After a few hours, he tired and his wife Betty took him home. That night, he suffered a massive stroke and never regained consciousness. He’s buried in Tulsa beneath a plaque with the inscription, “Deep Within My Heart Lies a Melody,” the first line from “New San Antonio Rose.”

He was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in the Early Influence category in 1999, and was given a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Recording Academy at the 2007 Grammy Awards, where Carrie Underwood sang “San Antonio Rose.” Every April since 1972, thousands of pilgrims from around the world have converged on Turkey, Texas, to celebrate Bob Wills Day. Young and old dance to Western swing bands, jam with other musicians, listen to talks by Wills scholars and musicians who played with or were inspired by Bob, and commune with kindred spirits.

Still, it’s hard for those who weren’t there to understand how big Bob Wills was in the Southwest and western U.S. during the Depression and throughout the 1940s. It can also be hard to hear the connections between his music and much of what has followed. Certainly there are the obvious heirs — Nelson, George Strait, Asleep at the Wheel — but Playboy alum Bobby Koefer, who followed Herb Remington and then Billy Bowman on steel guitar in 1951, sees his influence elsewhere. “Many earlier European artists, including Eric Clapton, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were influenced by Bob’s early blues and rhythm,” Koefer explains. “And today, whether it’s pop, rap, country, the basic rhythm could have been played by Bob Wills. Many musicians are still trying to get that sound.”

For Townsend, Wills’ greatness goes beyond music. “What attracted me, a poor and ignorant boy, is that it was nearly always fun and uplifting and made you feel good,” he says. “He was at his most popular when we were in a Great Depression and in World War II, when people needed him. He would lift them up, maybe for only 30 minutes, but he made them feel good, he made them happy.

“His greatest contribution — aside from creating a new kind of music — is that he lifted people up.”