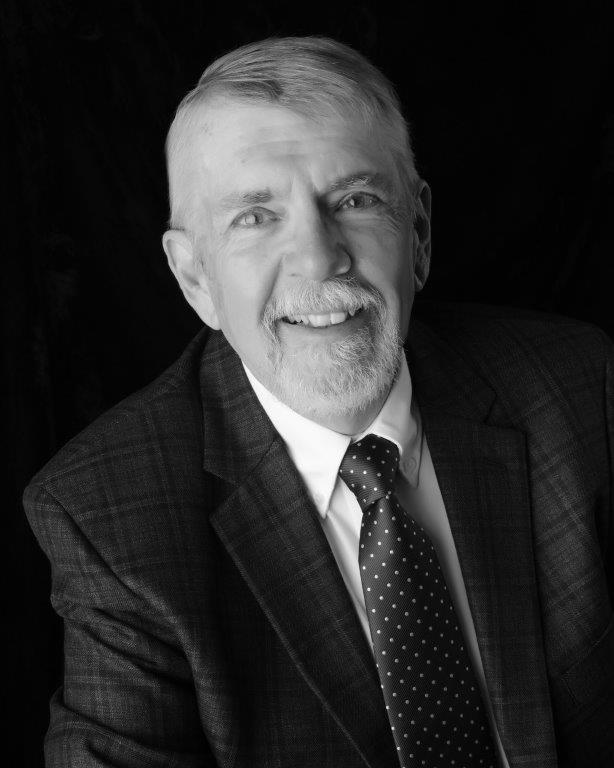

“Prolific” cannot begin to describe Mike Cox, the celebrated Texas author of more than 30 non-fiction books and hundreds of magazine articles, newspaper columns and essays. Now at age 72, the Amarillo native continues to tackle massive writing projects and, in so doing, uphold family traditions.

“My grandfather was a longtime newspaperman and spent more than 60 years as a freelance writer,” Cox says. “His daughter also worked for a time as a reporter. In fact, she met my future dad, who was a reporter in Amarillo, while covering a sensational murder trial – as competitors – in Sweetwater. I tell people I’m the product of two of man’s more singular acts, one of them being murder.”

His granddad and parents eventually moved on from daily journalism, but all of them continued for the rest of their lives as freelance writers. By the time he was 10, Cox knew he wanted to join the “family business.” He started writing in high school and sold his first magazine article to The Cattleman in 1964 for a whopping $35. His first newspaper job was writing a high school news column at $5 apiece for the Austin American-Statesman in 1965.

Cox worked as a full-time reporter at the San Angelo Standard-Times while majoring in journalism at Angelo State University, “a fact reflected in my GPA.” In the fall of 1969, having moved northward to the larger Avalanche-Journal in Lubbock for a bigger paycheck, he transferred to Texas Tech University. “The following spring, I helped cover the aftermath of the devastating Lubbock tornado, which killed 26,” he recalls. “At the end of my junior year, missing water, trees and 35-cent longnecks, I moved back to Austin to go to work for the American-Statesman.” He dropped out of the University of Texas his senior year in favor of a day job on the newspaper, but in his early 40s, he went back to college at Texas State University in San Marcos.

“I had 130 hours or so of credits but never graduated,” he says. “Now I laughingly tell folks I’m holding out for an honorary doctorate. I regret I didn’t get that piece of paper, but someone whose judgment I respect once told me that each of quite a few of my books would amount to a doctoral dissertation given the amount of research that went into them.”

Of the many books he’s authored, Cox won’t say which one is his favorite because it’s like asking a parent which one of their children they like best. Yet he’s quite proud of his two-volume, 250,000-word history of the Texas Rangers, which was published in 2008-2009 and continues to sell well.

“In my history of the Rangers, with apologies to Clint Eastwood, I tried to tell the good, the bad and the ugly,” Cox says. “At times, the 19th– and early-20th-century Rangers got out of line, but I think they did more good for Texas than bad. Lately, it’s been popular to villainize them, but I think the truth – as with most things – is somewhere in middle. I favor truth in history, but not taking down monuments. Monuments enable future generations to be able to talk about the heroes and the bad guys. It’s important to know both.”

Another of Cox’s favorite books is Train Crash at Crush: America’s Deadliest Publicity Stunt. “It’s the story of the so-called Crash at Crush, in which the old Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad deliberately crashed two obsolete steam locomotives head-to-head,” he explains. “The idea was to make money from the sale of excursion tickets to a special venue the railroad built near the small town of West north of Waco. Some 40,000 to 50,000 people descended on the hastily constructed depot named for William G. Crush, the railroad official who spearheaded the event, making it the largest ‘city’ in Texas for the day.

“The crash took place on Sept. 15, 1896, and would have been – pun intended – a smashing success except for the fact the locomotive boilers exploded, sending hot shrapnel flying into the crowd, but amazingly, only two people died as a direct result of the collision. My book about the crash is under option for a possible movie, but we’ll see.”

One of Cox’s best-sellers is a true crime book, The Confessions of Henry Lee Lucas, the notorious serial killer.

“For better or worse, I helped make Lucas infamous,” Cox says. “In the summer of 1983, I got a tip from an Austin homicide cop that a possible serial killer was in jail in Montague County, so I flew to North Texas the same day to look into it. I happened to be in the courtroom when Lucas first blurted out that he had killed 100 women. The next day my story – rewritten by the Associated Press – attracted national and international interest. Later, when Lucas was in the Williamson County Jail in Georgetown, the sheriff let me interview him in his cell. For a while, I had a standing Tuesday night ‘date’ with Lucas.”

Cox ultimately got a call from an editor in New York asking if he’d like to do a book about Lucas. A revised 30th anniversary edition of that book, renamed The Confessions of a Killer, was published in the spring of 2021.

Cox jokingly says that he writes “just about anything someone will pay me for.” Actually, he’s written everything from biography to folklore to history to a book on commercial diving. “The only thing I haven’t done is fiction,” he notes, “and at this point in my career, though I always thought I’d eventually write a novel, I doubt that I’ll ever get around to it. But who knows? Maybe someday.”

His “problem” is having more ideas than he can handle. He grew up hearing good stories from his grandfather and parents, and he’s been seeking good stories ever since. When he decides to pursue a particular topic, he’s inclined “to over-research my books” because he loves “the thrill of the hunt when collecting material for a magazine article or book,” a habit he developed in his newspaper days. When it’s time to write, he strives for a conversational, interesting style, with a little humor thrown in when it’s appropriate.

Writing has been the central theme of Cox’s career, but there have been other fascinating chapters along the way. After almost 20 years as a newspaperman, he became spokesman for the Texas Department of Public Safety in 1985.

“During that time, I was the guy you saw on TV, heard on the radio or quoted in the newspaper any time something terrible or weird happened in Texas, which was quite often,” he says. “One of my worst experiences was handling the 1991 mass murder at the Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen. Not long after the shooting stopped, I was walking among the bodies of the victims trying to get information to provide to the media.

“But that was nothing compared to the 1993 Branch Davidian standoff in McLennan County near Waco. There were some 500 journalists from around the world, and the pressure was intense. I wanted to tell the public as much about it as I could, but the Feds wanted me to say as little as possible. I was involved significantly after the fire when the Texas Rangers were trying to get to the bottom of what happened.”

He later served as communications manager for the Texas Department of Transportation before retiring in 2007. Retiring from retirement in 2010, he went back to work as spokesperson for Texas Parks and Wildlife. He left the 8-to-5 world for good in February 2015 to write full time from his home in Wimberley.

Cox firmly believes “the writing life is a great life,” and in his case, the rewards – and awards – have been significant. In 1993, he was elected to the Texas Institute of Letters, an honor society founded in 1936 to celebrate the state’s most-respected writers. He was awed to be inducted the same year as journalist Bill Moyers and novelist James Michener.

In 2010, Cox received the A. C. Greene Award, presented annually by the Abilene Public Library to a distinguished Texas author for lifetime achievement. The honor was all the more special since Cox knew Greene, an author, columnist and Abilene native. Cox also earned a Will Rogers medallion in 2014 for his book about Dean Smith – Cowboy Stuntman: From Olympic Gold to the Silver Screen.

For the benefit of up-and-coming writers, Cox has donated his writing-related papers including correspondence and research material to the Southwest Writers Collection at Texas State University and to several other Texas universities.

“What I am most proud of is that the fast-growing San Marcos Public Library agreed several years ago to accept my Texana collection, some 6,000-plus Texas books,” he says. “The collection’s named after me and gives the San Marcos library a college- or small university-level resource. As a longtime book collector, I was very relieved to know that the collection I worked so long to build would not be broken up in an estate sale someday.”

As for other book topics he’d like to pursue, Cox claims to be afraid of running out of time before running out of ideas. He’s working on an ambitious series of five books called Finding the Wild West. They’re travel guides to all 23 states west of the Mississippi, broken down by region. He got the idea from his best-selling Gunfights and Sites in Texas Ranger History, published in 2015.

He’s also under contract for Wicked San Antonio, which spotlights little-known scandals and crimes in the history of the Alamo City, including the West’s last train robbery – the 1970 holdup of the miniature Brackenridge Eagle in Brackenridge Park. In addition, he’s working on a memoir about his family’s three-generation newspaper story, Blood and Ink.

Cox just finished a how-to book called Seven Million Words: Writing and Selling Nonfiction. The title comes from the number of words he estimates he’s put down on paper or up on a computer screen over the years. “Writing has afforded me many experiences most people never have,” he says, “and hopefully, as I get older, writing will continue to keep my mind as sharp as possible. In a nutshell, my advice to anyone wanting to become a writer is simple as 1, 2 with no 3. Read a lot, and then start writing. You learn to be a writer by keeping at it, day after day, whether you feel like it or not.”

By keeping at it, super-prolific, award-winning author Cox might have to change his “nickname” of “Seven-Million-Word Man” to an even loftier number. His avid readers certainly hope so.