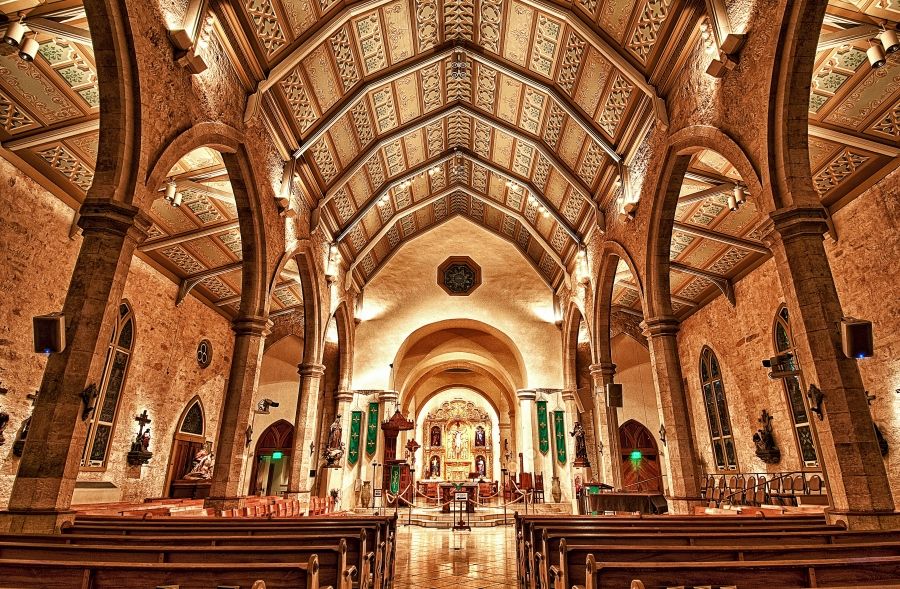

Just short of a mile from the Alamo’s front doors stands an equally proud, majestic structure — whose walls tell not the story of folk heroes or conquistadors but of the countless generations of faceless, faithful Texans who — for nearly three centuries — have made San Antonio their home. As far as historical landmarks go, the Cathedral of San Fernando is unique. Unlike the crowded plaza of the Alamo or the quiet fields of former Spanish missions, the Cathedral offers its visitors something beyond a brief, albeit meaningful, snapshot into our state’s proud history.

At the Cathedral of San Fernando, history, rather than being passively observed, is made every day by parishioners and visitors alike.

Truly more than just the city’s religious center, the Cathedral of San Fernando has long offered a sense of identity to both San Antonio’s pious and lay populations. “Being the oldest cathedral in the United States, there’s a long-standing sense of history there, sure.” says Timothy Matovina, a religious scholar who’s spent a great deal of his professional career observing the continuing history of San Fernando and her faithful parishioners. “It’s not just a history, though — it’s a living legacy, a tradition. Its people know that San Fernando is where their rituals, their devotions, their communal life has been celebrated and valued for many years.”

It’s easy to see why generations of San Antonians find such a comforting sense of tradition in San Fernando, especially when one considers how deeply rooted the Cathedral is in Texas history. Construction on what would ultimately become San Fernando Cathedral began in 1738, when 56 immigrants from the Spanish-held Canary Islands established Texas’ first organized civil government, the town of San Fernando — named for the future King of Spain, Ferdinand VI.

Built upon the exact geographical center of modern day San Antonio, the Cathedral would bear witness to crucial events of the Texas revolution. In 1831, frontiersman James Bowie married Ursula De Veramendi within the Cathedral’s walls. Not five years later, Bowie would witness Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna raise the symbolic red flag of “No Mercy” from the Cathedral’s bell tower — shortly before the ill-fated Battle of the Alamo. After the revolution, renovations began on the now dilapidated church. Carried out by architect Francois P. Giraud in 1861, these renovations included the construction of an extensive Gothic revival-style nave around the original colonial church, giving the Cathedral its current, European-influenced design. Today, the walls of the original 1738 colonial church form the Cathedral’s sanctuary, bestowing upon San Fernando the title of oldest continuously operated Cathedral in the United States.

Long since passed are the days of frontier revolution; at the end of the day, historic or not, San Fernando is still a Catholic institution — and an important one at that. Today San Fernando serves as the San Antonio Archdiocese’s central church, and the seat of its current archbishop, Gustavo Garcia-Siller. As it was in the 18th century, the modern-day religious leaders of San Fernando remain steadfast in their mission of sharing the word of God with San Antonio’s religious population.

One group that’s been historically receptive to the church’s mission is San Antonio’s Latino population. As former San Fernando rector Virgilio P. Elizondo wrote in the 1998 book San Fernando: Soul of the City — which he co-authored with Matovina — “In the past Tejanos were often denied entrance to many of the institutions of a city, state and nation, including Catholic churches. San Fernando has always been a parish home where Tejanos or Mexicanos have never had to explain who they are, why they are the way they are, or why they worship the way they do.” It’s this feeling of belonging that’s given San Fernando a reputation as a place where tradition is not only something to adhere to but to celebrate as well.

In addition to hosting Spanish language mass, the influence of its Latino parishioners can be readily found in the many extravagant celebrations held annually. “Latinos have a certain sense of joy connected with their coming together in worship” says Matovina. “San Fernando is a Catholic Latino faith community living out its traditions. Some things may change, but the deeper underlying spirit of it is still there.” Traditions that have been adhered to for generations continue to draw thousands to the center of San Antonio.

Events such as the Serenata a la Virgen de Guadalupe, San Fernando’s annual musical tribute to the virgin Mary, attract faithful parishioners to the Cathedral, while celebrations like Las Posadas — the church’s annual Christmas pageant — and the Easter Passion Play see hundreds of San Fernando’s parishioners spill into the streets of downtown San Antonio, recreating the birth and death of Jesus, respectively, for all to witness. “These celebrations have gained popularity because of the Hispanic population who’ve found their roots here,” says San Fernando’s director of religious education, Lupita Mandujano. Mandujano isn’t speaking just as an observer but as a living example of the church’s continuing tradition. Having immigrated to San Antonio from Mexico as a child, Mandujano has been a lifelong parishioner of San Fernando. It was during one fateful Las Posadas pageant that Mandujano — portraying the role of the virgin Mary — met her husband Mario, who, fittingly, played the role of Joseph. Years later, Mandujano would reprise the role of Mary in San Fernando’s Easter Passion Play, this time alongside her grown son, who portrayed Jesus. “It’s the language of tradition that keeps San Fernando alive,” Mandujano says. “It’s like my second home.”

This seemingly effortless ability to attract devout Latino parishioners of all ages serves as a reflection of the Cathedral’s history of inclusiveness and acceptance. Though devoutly Catholic, San Fernando’s leaders have long made it their mission to provide a sense of belonging to all peoples of San Antonio. “San Fernando today is a 300-year synthesis of coming together,” says Matovina. “People bring their own unique richness that together makes up a whole greater than the sum of its parts.” This synthesis is perhaps most apparent in the Cathedral’s annual Interfaith Thanksgiving Service. At this decades-old celebration, it’s not uncommon that Buddhist chants, Muslim calls to prayer, traditional Native American ritual dances and performances by African American gospel choirs are all observed under one roof. “We bring in all the traditions and cultures. It’s necessary to recognize that we’re all one humanity,” says Father Victor Valdez, current rector of San Fernando parish. “Through the church’s teachings, you see how God has placed gifts in all faiths. We use that as growth, to help mature in our own faith as well.”

While it’s easy to understand why San Fernando is famous among San Antonio’s diverse citizens, in recent decades, due in part to the invention of new kinds of communication technology, the prominence of San Fernando has been extended far beyond the city limits. In 1983, the church began televising its masses on the Spanish-language network Univision, a practice that continues today. “That’s what put us on the map, even more so than before,” says Mandujano. “People wanted to see the Cathedral for themselves. Mass began to grow, but so did the Passion Play, which was also televised.”

With masses being broadcasted to viewers across many states and even other countries, San Fernando was effectively transformed overnight into a point of Catholic pilgrimage. “People loved it,” says Matovina. “Parishioners were always proud of the Cathedral, but to have San Fernando become a place where mass went out to the sick, the needy, people without Spanish mass in rural areas — it was a tremendous source of pride for the parishioners to celebrate the richness of their traditions with people from so many other places.”

Its televised mass made the Cathedral a popular destination among Catholics, but it would be the groundbreaking work of one internationally renowned visual artist who’d solidify San Fernando’s status as one of world’s most intriguing tourist destinations.

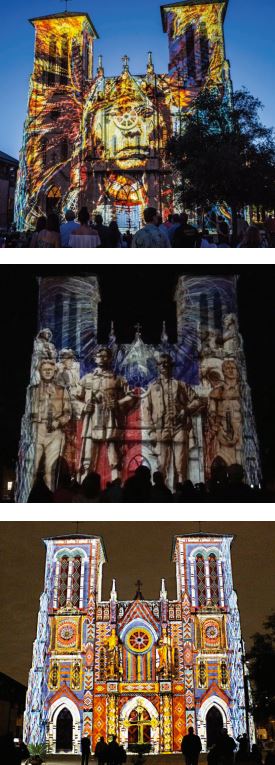

On June 15, 2014, an excited crowd of proud San Antonians gathered at the foot of the San Fernando Cathedral. It was here that acclaimed French painter Xavier de Richemont unveiled his latest creation, San Antonio: The Saga — a 24-minute “video painting” recounting the story of San Antonio’s history — projected onto the front facade of the Cathedral.

A sensory experience that must be seen to be believed, San Antonio: The Saga combines striking visuals with intricately coordinated sound design to bring the story of Texas to life. Making the most of its sacred canvas, the projection’s brilliantly colorful patterns and historical images dance in perfect unison around and on top of the Cathedral’s intricate architecture —injecting life and rhythm into the Cathedral’s deeply detailed features. “Xavier has designed the artwork to actually fit every nook and cranny of the Cathedral. Everything had to line up absolutely perfectly,” says Jane Pauley-Flores, executive director of the Main Plaza Conservancy — the nonprofit responsible for bringing Richemont’s vision to life. “When the sound is coming at you, and you’re seeing these incredible visuals, you truly feel like you’re one with the entire production.”

Needless to say, creating this one-of-a-kind experience wasn’t a simple undertaking for anyone involved. For the Main Plaza Conservancy, securing an artist as notable as Richemont for this project was a long shot, to say the least. “It was just so unusual. We were bringing the first piece of its kind to the United States,” says Pauley-Flores, “Xavier has works all around the world. Countries and governments hire him. And here was just a simple small nonprofit down in the center of San Antonio trying to achieve what whole countries were achieving.” Luckily for the Conservancy’s board of directors, Richemont — who has long had an interest in American history — was receptive to the idea, though complications for the Conservancy didn’t stop there. “It’s one thing to raise $50,000, because that’s a lot and it’s hard to do. But to raise over a million dollars? That’s staggering. It ultimately took the whole two years that Xavier was creating to raise that money.” While Pauley-Flores and her board got to work securing the necessary funds, as well as Archbishop Gustavo Garcia-Siller’s blessing to present The Saga on the church’s facade, Richemont began his creative process.

Incredible visual and audio elements aside, perhaps the most astounding aspect of The Saga is the amount of research that went into every single frame. Long before The Saga’s first sketches were created, Richemont undertook a monumental research process in order to acquaint himself with San Antonio’s rich history. “To truly understand another person is to spend time with him or her,” says Richemont, speaking symbolically, “You have to be humble. You have to listen very carefully to the stories people tell you. ” During the course of his research, Richemont would visit constantly with San Fernando’s Archbishop and rector, as well as countless other religious and historical scholars. In addition to these meetings, Richemont would spend hours visiting the city’s museums and historical missions. “To learn that much took me quite a few trips,” he explains. “I flew from Paris to San Antonio maybe six times.”

Needless to say, Richemont’s research process paid off. Guiding audiences on a visual journey from the early, pre-colonial days of Texas to modern times, Richemont has jam-packed The Saga with so many historical details that audiences often find themselves still picking out subtleties on their third or fourth viewing. Hundreds of flags, portraits and structures fly across the Cathedral’s face during The Saga, as centuries of Texas history are condensed into less than half an hour. For an artist as precise as Richemont, every detail of The Saga is intentional, no matter how small. “I’ve gotten so many emails saying, ‘I recognize this face in The Saga, but I can’t put a name to it. Can you tell me who it is?’” says Pauley-Flores. “All those questions coming in resulted in us actually publishing a coffee table book breaking down The Saga slide by side—it’s that detailed.”

Since its premiere in 2014, The Saga has received numerous accolades, including being named “Best of the City” by San Antonio Magazine. “We have people not only coming from all over the country,” says Pauley-Flores, “but because of our international recognition and awards, people will call my office from other countries, saying they’re planning their entire vacation around seeing The Saga.” The Saga continues to show three times a night, four nights a week, on San Fernando’s facade — completely free and open to the public — and will continue to do so until at least 2024.

Maintaining the parish of a church that draws hundreds of visitors daily, for both religious and non-religious reasons, may seem like a daunting undertaking. Fortunately, for the Cathedral’s leadership, balancing the religious and the secular is one of San Fernando’s many long-standing traditions. “During mass we’ll have lots of people come by who are just visiting. We’ll have our ushers invite them in, to stay and witness the mass,” says Father Valdez. “I’m always telling people to come see The Saga. I’ll even push it! Part of building up spirituality includes making that connection with the secular. I’m constantly asking myself, ‘How can we use these attractions to help people?’”

In addition to making these connections, the leaders of San Fernando also continue what is perhaps the church’s most valuable tradition: providing a unified sense of identity to all of San Antonio’s people. “That’s what people like about San Fernando,” Motavina says. “Here, they feel they’re deeply rooted in something so much larger than themselves.”