On the longest barrier island in the world, in extreme south Texas, South Padre Island is maybe best known for Spring Break and outstanding beaches, but it also has a long and varied history.

As part of the “New World,” South Padre Island, also known as “Isla Blanca” (the White Island), found itself under the ownership of Spain, Mexico and then the Republic of Texas before Texas became a state in 1836. Shifting sands, and a lack of fresh water and other resources made for a challenging environment, and the area wasn’t permanently settled until around 1804, when Spanish priest Padre José Nicolás Ballí arrived.

Ballí’s family had migrated from Spain more than 235 years earlier. In 1800, Ballí applied to King Charles IV of Spain for 11.5 leagues of land on the island and started its first settlement, Rancho Santa Cruz. Padre Island came to be named in his honor.

Ballí’s cattle ranch was headquartered on South Padre Island until about 1810. Up to this point the most frequent visitors were the local, if not nomadic, tribes of Karankawas, who were adept at traversing the tough conditions, finding food and sustenance. The Karankawas, or “Kronks” as they were informally known, weren’t hospitable. The crew aboard the 1554 shipwreck off South Padre Island found this when they met the Karankawas repeatedly as they struggled to make their way inland. Of the 300 sailors who survived the shipwreck, only one survived the trek.

The Karankawas and other local tribes knew how to camp and fish and pillage wreckage that washed ashore. In the 1740s, Spanish colonizer José de Escandón’s men were forced to retreat from the beach as the tribe threatened the frightened Spaniards with bows and arrows. During the winter the Karankawas would migrate to the interior of Texas, where they hunted, and then would return to the coast in the spring to feed on local delicacies such as prickly pear cactus and seafood. The prickly pear cactus was rolled in the sand to remove the thorns and then were eaten like apples or dried like figs to be consumed later. Bays and inlets were navigated by poling in dugouts. Redfish were shot with bow and arrow and shark hunted and killed by knife. It was possible to thrive on this island, but special skills and knowledge were clearly necessary.

John Singer and his family arrived in the South Padre Island area in the mid-1840s. The Singers bought Santa Cruz Ranch from Padre Ballí and built their home on the foundation of the Ballí home, then in ruins. They renamed the ranch “Las Cruces.” Eventually the area became known as the Singer Ranch. Singer was appointed wreckmaster — the need for such was an indication of the treacherous waters off the coast. Salvaged materials amassed on the homestead site and were buried in what was called “money hill.” When the U.S. Civil War broke out in 1861, the Singer family, being Union sympathizers, involuntarily relocated to the Flour Bluff area up the coast near Corpus Christi. The unknown status of their buried treasure is still a topic of conversation and research — and search. Countless shipwrecks along the coast of South Padre Island brought opportunity to gather jewelry and coins of untold value.

As a barrier island on the Gulf of Mexico, South Padre Island has also found itself in the path of numerous storms and hurricanes. Just before Ballí’s arrival, in 1791, upwards of 50,000 head of cattle succumbed to a ferocious hurricane. In 1933, a series of storms and hurricanes so ravaged the area that some said only the peak of the lighthouse in Port Isabel was visible above the water.

But the lure of fresh sea breezes and the beautiful sandy beaches and the uniqueness that makes South Padre Island such a sought-after destination eventually shaped its history and set its future. Since the days in the late 1740s when José de Escandón was sent by Spain to colonize both sides of the Rio Grande, part of the area’s appeal was the proximity of South Padre Island and the relief it promised from the harsh summer temperatures. That’s still the lure.

To get to the island from the mainland one had to traverse the Laguna Madre Bay. One of the largest hypersaline bays in the world, the Laguna Madre has an average depth of 24 inches. Before the construction of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, which cut a channel through it, it was possible to wade from the mainland to the island when the tides ran low. The Karankawas could make their way across on foot or by dugout. To get to the island via the Gulf of Mexico, most seafaring vessels made their way from New Orleans and landed on Brazos Island, just across the Brazos Santiago Pass south of South Padre Island.

About a century ago, when tourism and development were beginning to heavily impact the area, transportation to the Island birthed the ferry business in Port Isabel. Passenger ferries could be secured on the bay front in Port Isabel, and passengers shuttled across the bay to the island. Or one could catch a schooner off the 1,500-foot railroad dock for a sail across the bay. Soon, ferries that could accommodate automobiles were added, and for $2 you could take your car with you.

Still with limited infrastructure, roads on the island were scarce, so strategy on the sand was a must. South Padre Island was becoming a beach and recreation destination. A casino and several hotels were constructed in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and restaurants opened. Militarysurplus halftracks were ferried to the island to offer transportation over the sand dunes. Passenger trains from Brownsville extended schedules during the summer months so every last minute could be spent on the beach before catching a ferry back to the mainland and then a train to Brownsville.

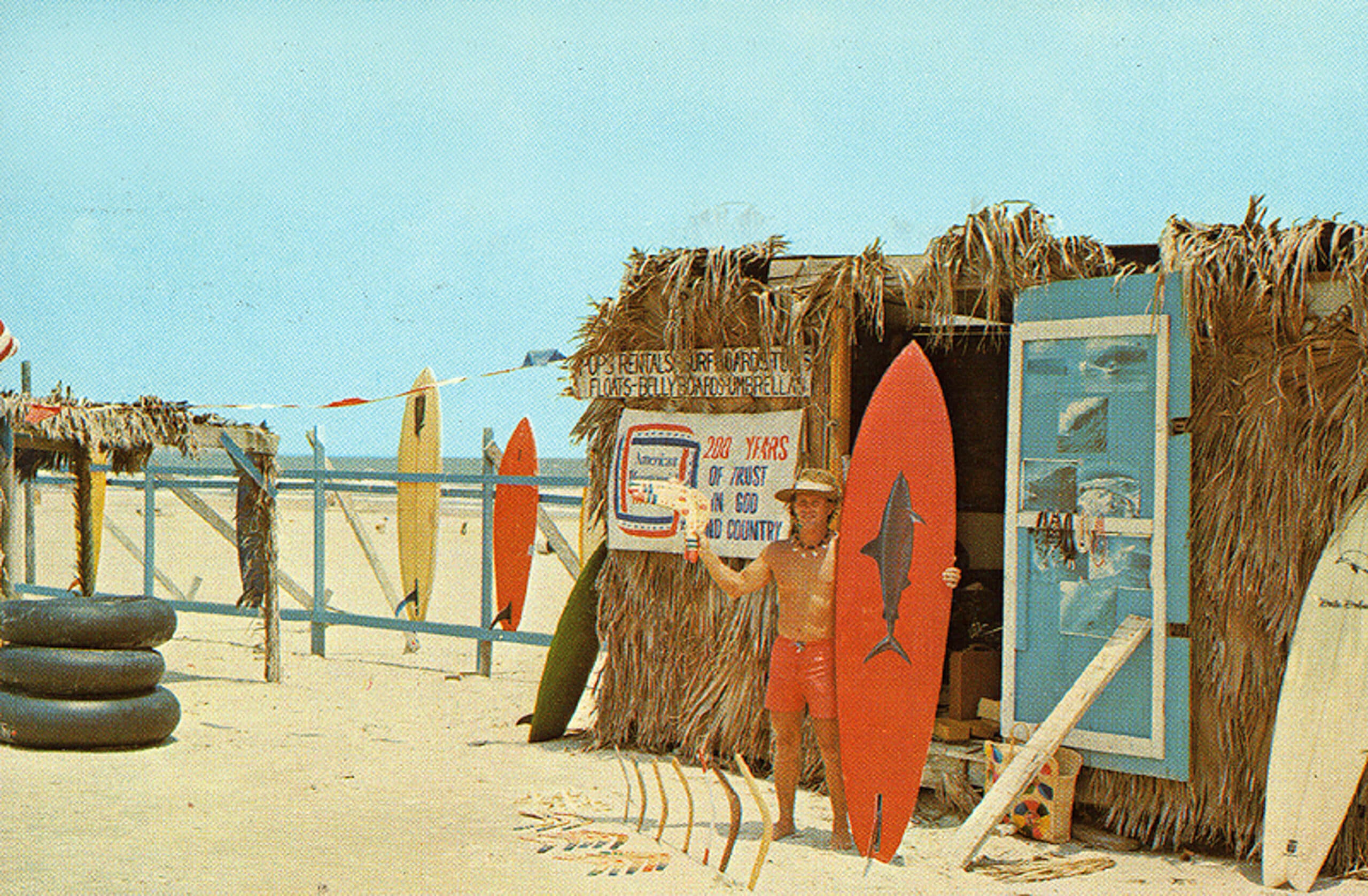

Spring Break, a tradition that dates to the 1930s, soon found a home on South Padre. The trend peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with tens of thousands of Spring Breakers flocking to the island to enjoy the weather and the waves. Spring Break has a multigenerational impact, as visitors frequently return to the area with their families to vacation or to relocate.

In 1954 a causeway was built to connect South Padre Island to the mainland. The grand opening brought thousands of vehicles and passengers who waited in line to drive to South Padre Island on the two-lane bridge. The $2.2 million causeway was dubbed a masterpiece of steel and concrete. It extended 15,272 feet from downtown Port Isabel to the southern tip of South Padre Island across the Intracoastal Canal and the waters of the Laguna Madre. The bridge was constructed of shellcrete and was short-lived. In 1974 the original causeway was retired and a new bridge was opened, also named the Queen Isabella Causeway. Four lanes and 2.6 miles long, the new Causeway became the longest bridge in Texas and doubled traffic capacity. The lure of the pristine sandy beaches of South Padre Island was not to be denied.

The town of South Padre Island incorporated in 1973, and a building and development boom commenced. With water-park resorts, a World Birding Center, accommodations, county and city parks, jetties, miles of publicly accessible beaches and activities that include fishing, shopping, dining, parasailing, paddle boarding, sailboarding, kite flying, surfing, boating, kayaking, jet skiing, dolphin watching and more, South Padre Island is a destination that holds the key to adventure. And while the South Padre skyline is in a constant state of change, the simple tradition of a trip to the beach — to one of the top beaches in the U.S. — remains.