In the 1950s, the magazine Texas Parade wrote, “Not since Cheops erected his great Pyramid in Egypt, perhaps, has so singular a monument as the Texas highway system been engineered to one man’s dream.”

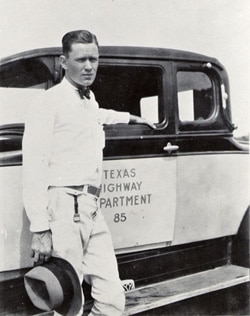

World War II had a major impact on the work of the Texas Highway Department (now the Texas Department of Transportation). The agency was designated as essential, meaning that its employees were not subject to the military draft. Dewitt C. Greer, who served as state highway engineer (1940–1967) highway commissioner (1969 to 1980) unsuccessfully protested the designation, and then attempted to volunteer himself, only to be turned away because he was deemed by the state as too essential to be spared.

But Greer was more than a technocrat: he was a visionary who would leave a permanent stamp on the landscape of Texas. As the decades passed, he lectured around the world on constructing modern highways that served “a civilization geared to motor vehicles.”

In 1947, Texas accounted for 25 percent of the highway construction in the entire United States. Over the next three decades, the department would win a reputation as one of the best in the nation. By the early 1950s, all 22,000 miles of the system Greer had inherited in 1940 was paved, and the highway system had been expanded to take in 24,000 miles of rural road. The Highway Department began to purchase rights-of-way and plan the construction of hub-and-spoke expressways to connect to the city centers of Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio. To better serve long-neglected farmers and ranchers, the Highway Department began to experiment with improvements such as hot topping, a process of improving gravel or dirt roads to withstand wet weather and heavy traffic.

Meanwhile, suburban life was something new for Texas, created in large part by the “civilization geared to motor vehicles” that Greer celebrated and that the Highway Department served. New superhighways, such as U.S. 77 near Gainesville and the Gulf Freeway between Houston and Galveston were regarded as engineering marvels that carried more traffic within months of opening than they were projected to carry in a decade.

Construction of the interstate system began in 1954. Texas was allocated almost 3,000 miles of the system (of 41,000 miles nationwide). The Texas interstates would include the mighty Interstate 35 and four east-west routes (I-10, I-20, I-30, and I-40).

Texas was not immune from the unforeseen consequences of this boom. Cities were cut in half by the huge highways, with lasting effects on geography, unity, and livability. Generations later, city planners still struggle to revamp downtowns drained of their vitality when historic neighborhoods, parklands, and scores of independent retailers, hotels, and movie theaters were cleared to make room for the roads. In addition, roadside businesses and entire communities that had sprung up to serve traffic along the older highways suffered severe economic fallout when the interstate passed them by. The new highways spawned their own economic culture of motel chains and fast-food eateries, including Texas-grown Whataburger and Church’s Fried Chicken.

In 1963, the Dallas Morning News published an insert describing the newly opened I-35. The paper predicted with sweeping optimism that the highway would eventually connect both continents of the Americas, from Cape Horn to Alaska (the present highway runs from Laredo, Texas, to Duluth, Minnesota).

In 1917, when the Texas Highway Department was created, much of the state remained largely an economic backwater, literally mired in the mud of roads scarcely any better than the rough frontier traces carved out by the Spanish pioneers four centuries earlier. By the time he retired in 1968, Dewitt C. Greer presided over a system of more than 68,000 miles of paved highway. He continued to serve as a highway commissioner for another dozen years. Texas was home to a modern highway system that had won worldwide fame for the Texas Highway Department and helped catapult the state into the leadership position in the rising economic powerhouse of the American South.

As you’re traveling Texas highways, don’t forget to stop at transportation history fun spots:

The Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum houses 200,000 square feet of history, including a permanent exhibit featuring a 1903 Ford Model A Runabout and the very rare 1910 Zimmerman Touring Car.

The Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

2503 4th Ave

Canyon, Texas

Panhandleplains.org

Hours: September through May: Tuesday-Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.,

June through August: Monday-Saturday, 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., Sunday 1:00 to 6:00 p.m.

The Horton Classic Car Museum is located in Nocona and features some of classic American cars. Nocona is about 90 miles north of Fort Worth, Texas.

Horton Classic Car Museum

115 West Walnut Street

Nocona, Texas 76255

Hours: Monday-Friday 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.; Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.

hortonclassiccarmuseum.com

The RV Museum features many vehicles including the 2006 Flexible Bus from the movie RV, starring Robin Williams, as well as the first Itasca motor home ever built, and some of the oldest Fleetwoods in existence.

Jack Sisemore Traveland RV Museum

4341 Canyon Drive, Amarillo

Hours: M-F, 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Sat 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.

rvmuseum.net

Adapted from TSLAC’s online exhibit, “From Pioneer Paths to Superhighways – The Texas Highway Department Blazes Texas Trails 1917-1968,” compiled by Liz Claire.